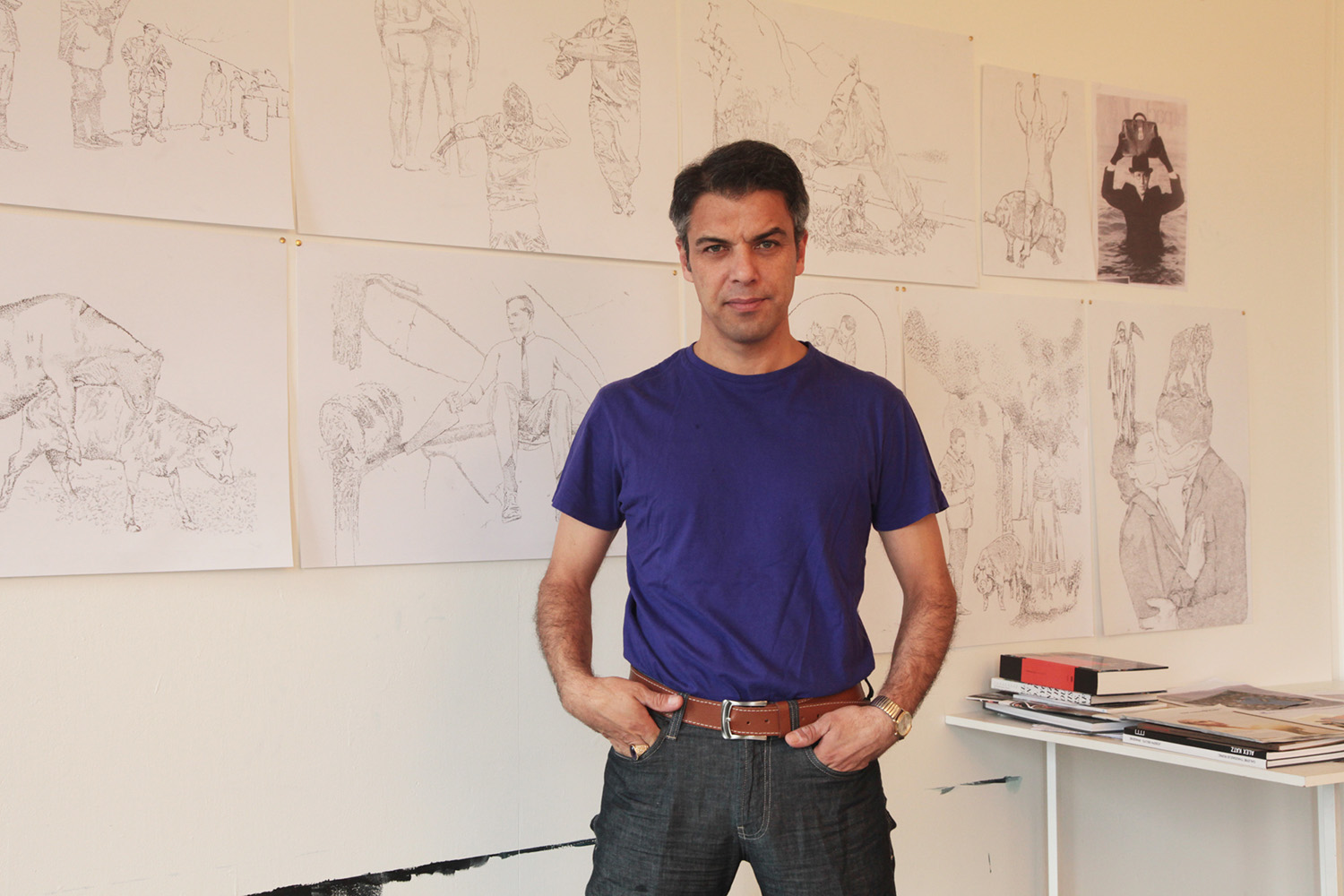

FERHAT ÖZGÜR & DERYA YÜCEL

April 2014, Istanbul

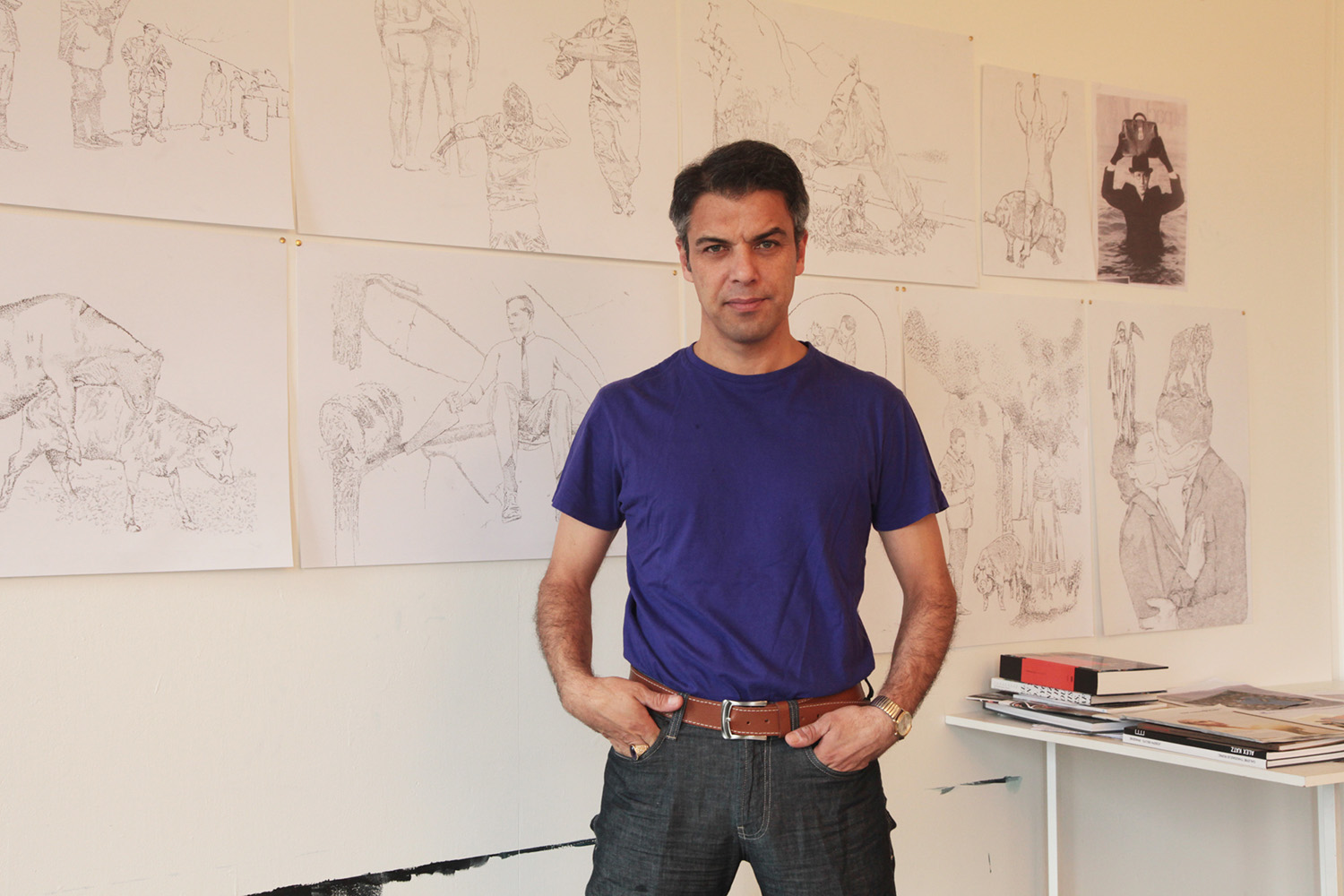

Derya Yücel: Your personal memory is often at the forefront of your work in which you address cultural phenomena such as borders and crossovers between centres and peripheries, immigration, religion, identity and the city. At the same time, you have always kept your refined approach in sharing your personal testimonies with the audience. “Curious Moments”, which is your first solo show in Turkey since 2008, offers an overview of the approaches central to your practice and the relations you establish between various media. In order to provide some background information I would like to start our conversation with some biographical details about you.

Ferhat Özgür: I was born in Ankara, where I also had my academic education. After graduating from Gazi University, Faculty of Education, Painting Department in 1989, I received my MA degree from Hacettepe University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Painting Department. I worked at Hacettepe University as a lecturer between 1993 and 2010, after which I moved to Istanbul. I spent most of my childhood and early youth around Altındağ, the district around Ankara Castle. That was a real slum area where mostly immigrants from central Anatolia settled and lived in extreme poverty. But I tend to refrain from such references as they could be incriminatory. I would say that, in general, I had a happy childhood. Regarding family relations, I have no childhood traumas that still haunt me. I had no oppression in my family, neither from my mother, nor my father who passed away at an early age, nor my siblings. But it is necessary to highlight the political and cultural climate of Altındağ, because it was a significant factor in my decision to study art and for me to identify what I am capable of. Interestingly, the street we lived in was in a strategic position. To the right side there was the Great Ankara Hospital, a place where German professors used to work in the 1930s, and its building had influences of German architecture. On the left side of the street, there was the Ulucanlar Half-Open Prison. I was about to start primary school when Yusuf Aslan, Deniz Gezmiş and Hüseyin İnan were executed there in 1972. Whilst playing on the streets, we would come across prisoners escaping from the prison and badly wounded patients coming to the hospital, both at the same time. It was almost like going back and forth between life and fiction. The older guys in an adjacent neighborhood were advocates of the rightwing/nationalist front while the nearer Aktaş quarter was leaning towards the left. Our neighbourhood Altındağ, being the middle region between the two, was one of the most volatile places in the 1970s when the conflict between right and left was most violent.

D.Y.: I know that growing up in these conditions has affected the way you formulated your artistic approach and your early works. While you were moving towards a certain direction in terms of content, you also experimented with different materials which heralded the variety of media in your later works. These could be considered as emerging points in your practice. Could you please talk about the effects of this period and environment on your artistic identity and the content and formal aspects of your work?

F.Ö.: In my childhood there was only one television channel. A cowboy film (“spaghetti western”) was shown every Sunday. For me and my friends in the neighborhood Sunday was the most exciting day! After watching these films we would go out immediately onto the streets and imitate the film, pretending to be cowboys! Most often I would take the role of an American Indian. Such a motive to imitate films must have not only offered me a way to experience life and fiction at the same time but also increased my interest in cinema. When eventually I decided to make art as a full-time profession, the Altındağ-Ulucanlar area formed the main ground for my works both in terms of content and form.

For example, during my educational years at the beginning of the 1990s, Zahit Büyükişliyen, my workshop professor at Hacettepe, had given an assignment to make a site-specific installation project. Such work was not common in Turkey in those years. As a prospective artist, who had never left Ankara and whose only experience of seeing art was limited to State Painting and Sculpture Museum exhibitions, competition exhibitions such as those organized by DYO (a private paint company), and a few artist books, I got really excited about this idea of a “site-specific” work. As I was living in a single roomed shanty (gecekondu) house and inspired by Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, I transformed my room into “The Room of a Young Poet” i.e. thousands of cigarette butts on the floor, scattered pieces of crumpled paper with scribbles and notes, books all around the place, a desk with a typewriter and a tea glass on it, etc. It was as if a young poet was trying hard to write a poem but he was not satisfied and he tore apart everything he wrote, throwing around the pieces of paper. He was in the throes of creation. We weren’t so well-aware of things then, so I don’t have any photograph of the space or layout of the work. I had shown the work to my professor at home as well. In those years, I had also seen a fascinating solo exhibition of Claude Viallat, one of the most important members of the “Support-Surface” movement, at Ankara State Painting and Sculpture Museum. That exhibition was a breaking point for me. I gained courage in a sense.

D.Y.: What kind of courage are you talking about? I will again ask you to relate this question to the influence of your living conditions on your art practice.

F.Ö.: Viallat had given up on framing and he was making meters long transportable paintings. The space I was living in was about 4-5 square meters altogether. I also wanted to play with large scale color marks and almost exhausted myself experimenting with things. I have so many beautiful memories of the following period: My mother would boil powder fabric paints in large boilers and I would get large pieces of fabrics from tent shops and scrap dealers in Ulus and plunge them into these boilers to give them color. And then I would play with the motifs and get random images by decoloring them with ozone. I could iron and fold these large size fabrics, store them in plastic bags and carry them over to wherever I wanted. The works were nomadic in a sense. At some point my friends said, “Oh, he is imitating Viallat,” but I was proud of that. I thought everyone should have a master.

D.Y.: And a source of inspiration. Your realistic and emotional connection with the neighbourhood you used to live in has been a source of inspiration to you for a long time. Kathryn Rhomberg, the curator of the 6th Berlin Biennial, described your photographic piece “Let Everyone Come Out Today” (2002) that you made on that street as “an oeuvre where all of your art works unite”. Again the same street was the leading role in this piece which you made in the years when you were moving towards photography and video! I think this piece has an insider’s view since you have inscribed this place in your memory, hence were able to engage with its reality as your own, as well as an outsider’s view that you created from a distance without exploiting the subject or being alienated.

F.Ö.: Yes, even after many years I was still frequently going to the street where I was born and grew up. My family was still living there. It was Sunday. I went there with my camera. I didn’t really tell anyone what to do. I knocked on the doors of all neighbors and I asked them to come outside because I knew that the street would not continue to exist and its residents would never come together in the same way again. “We will take a souvenir photo,” I said. I wanted them to experience a unique moment together. I lined them up along the street and photographed them both from the entrance and the exit of the street.

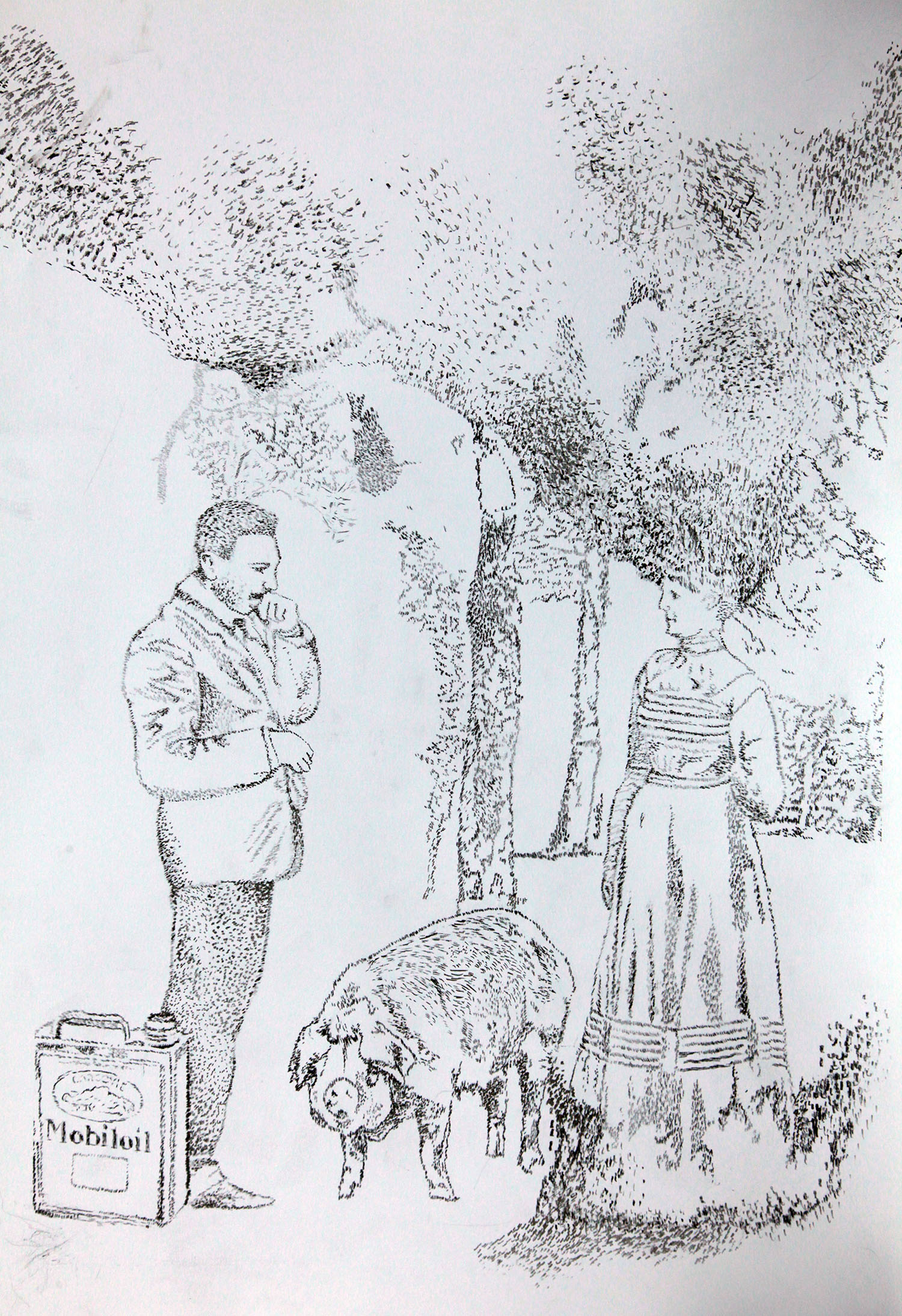

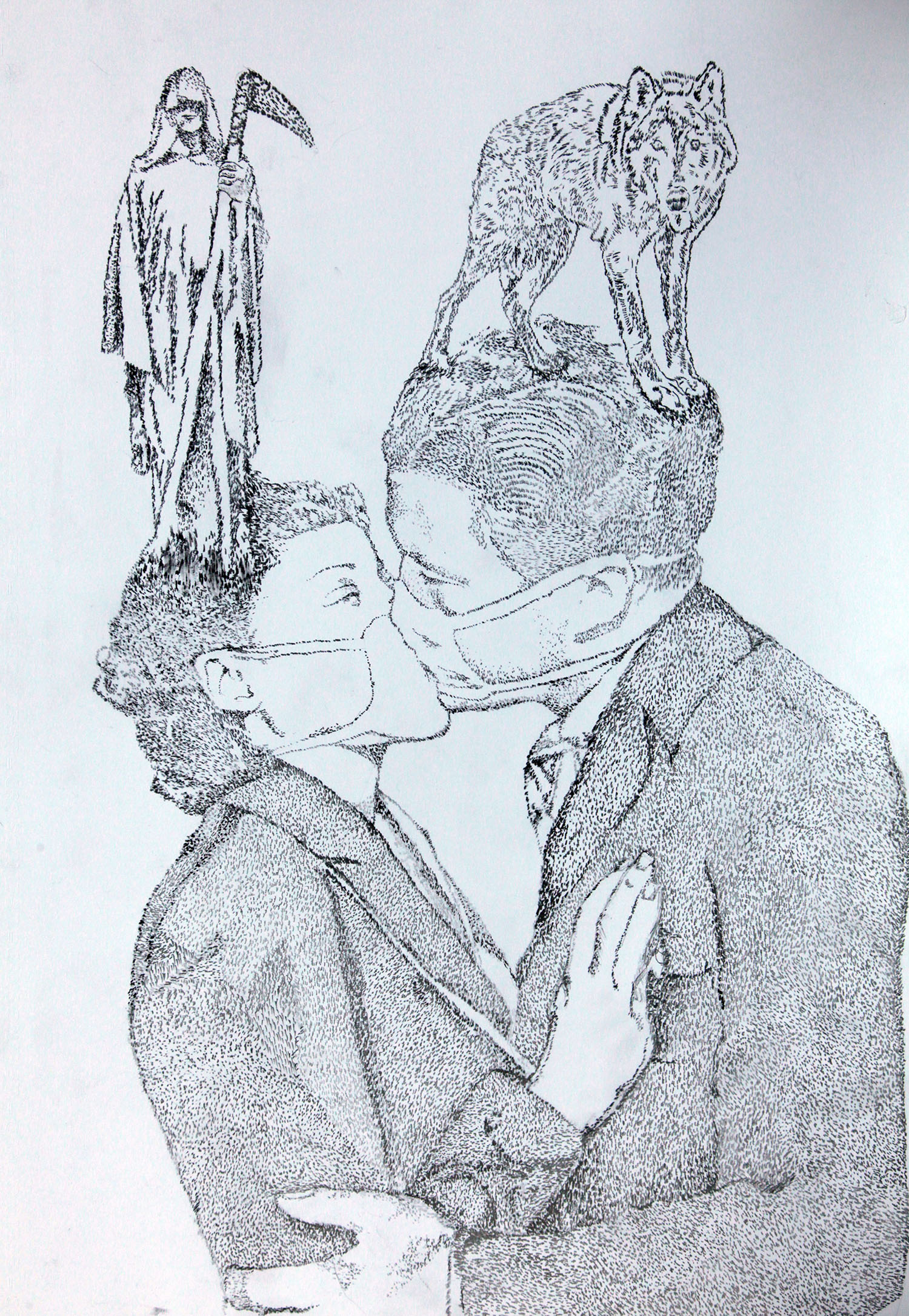

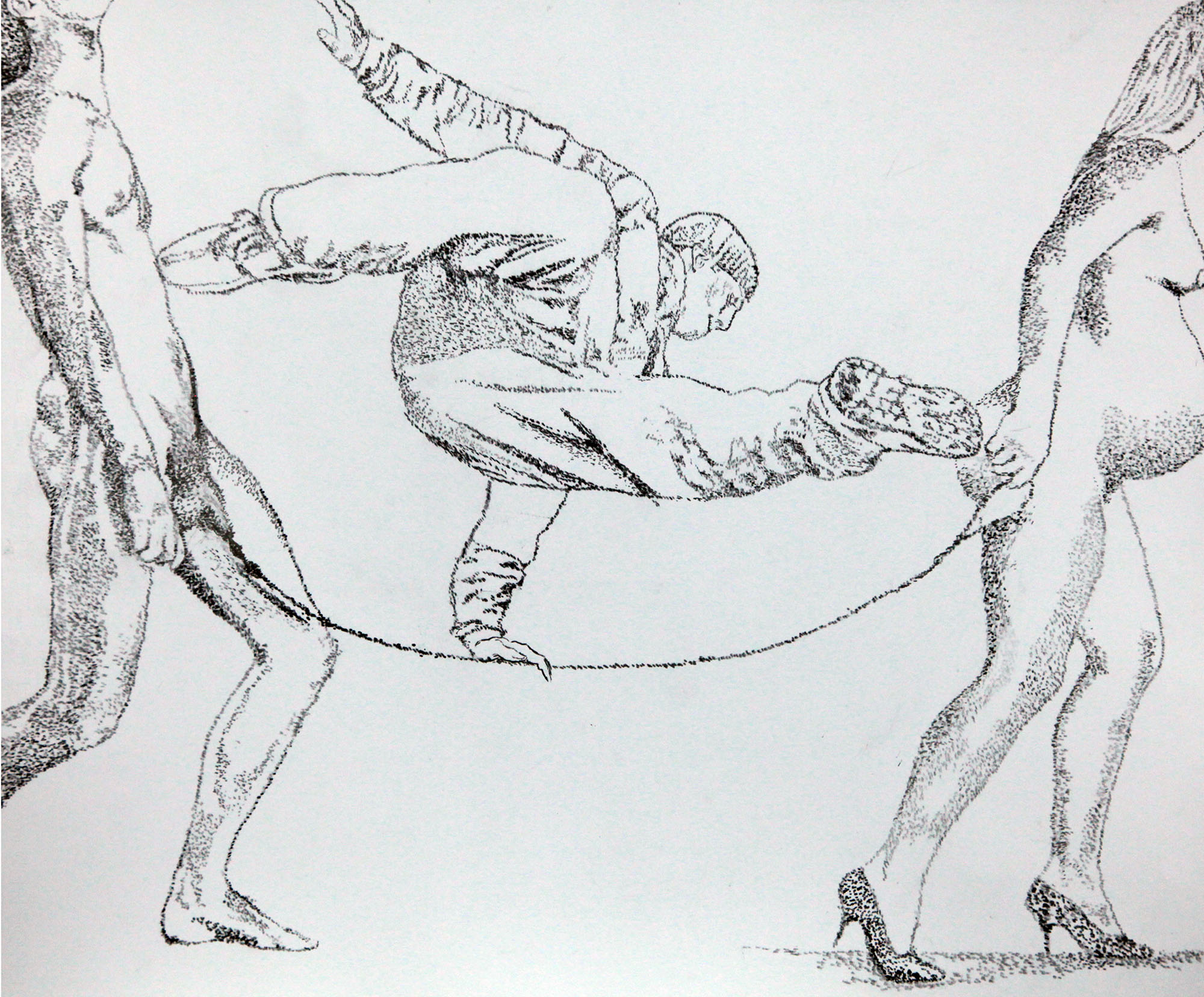

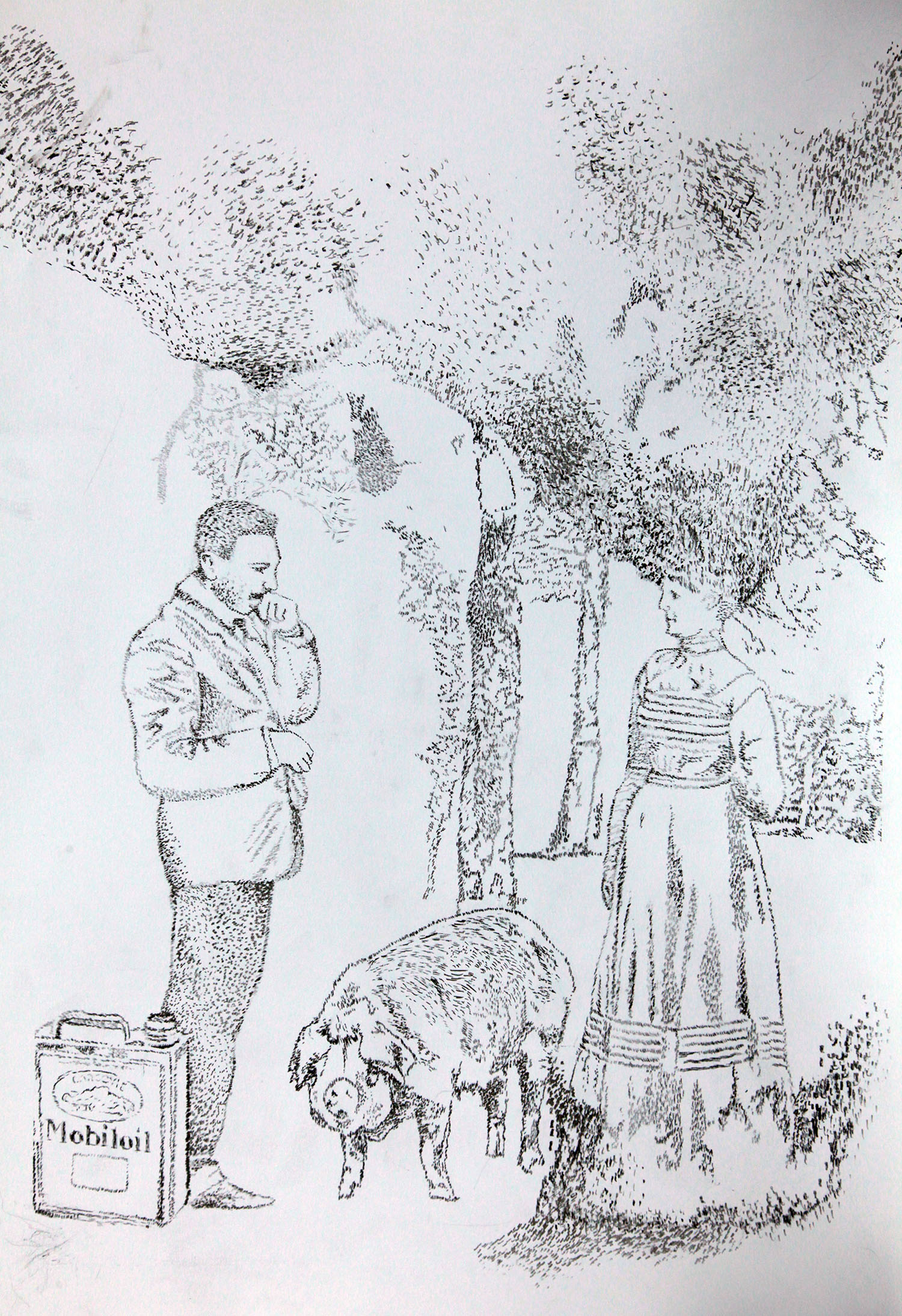

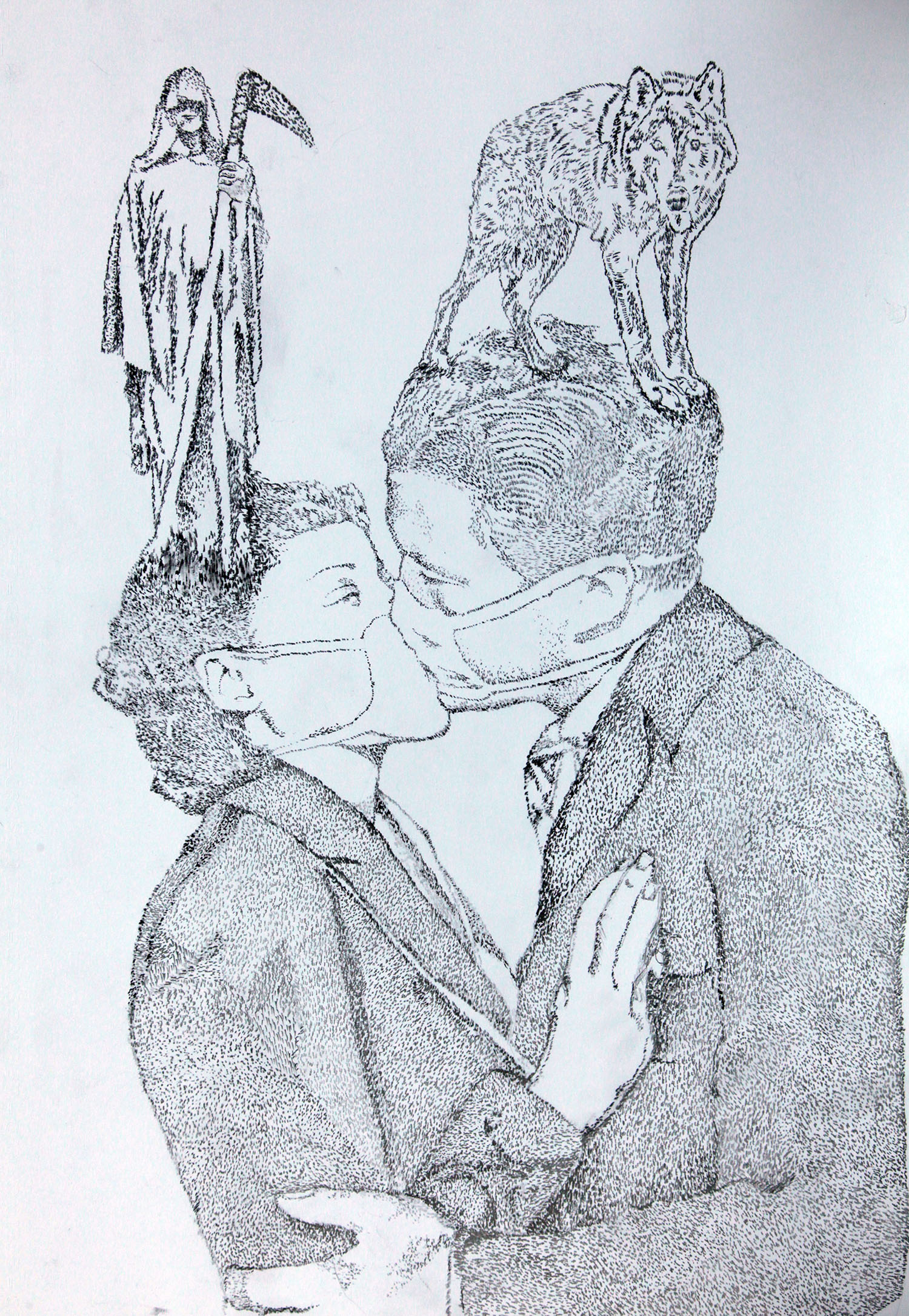

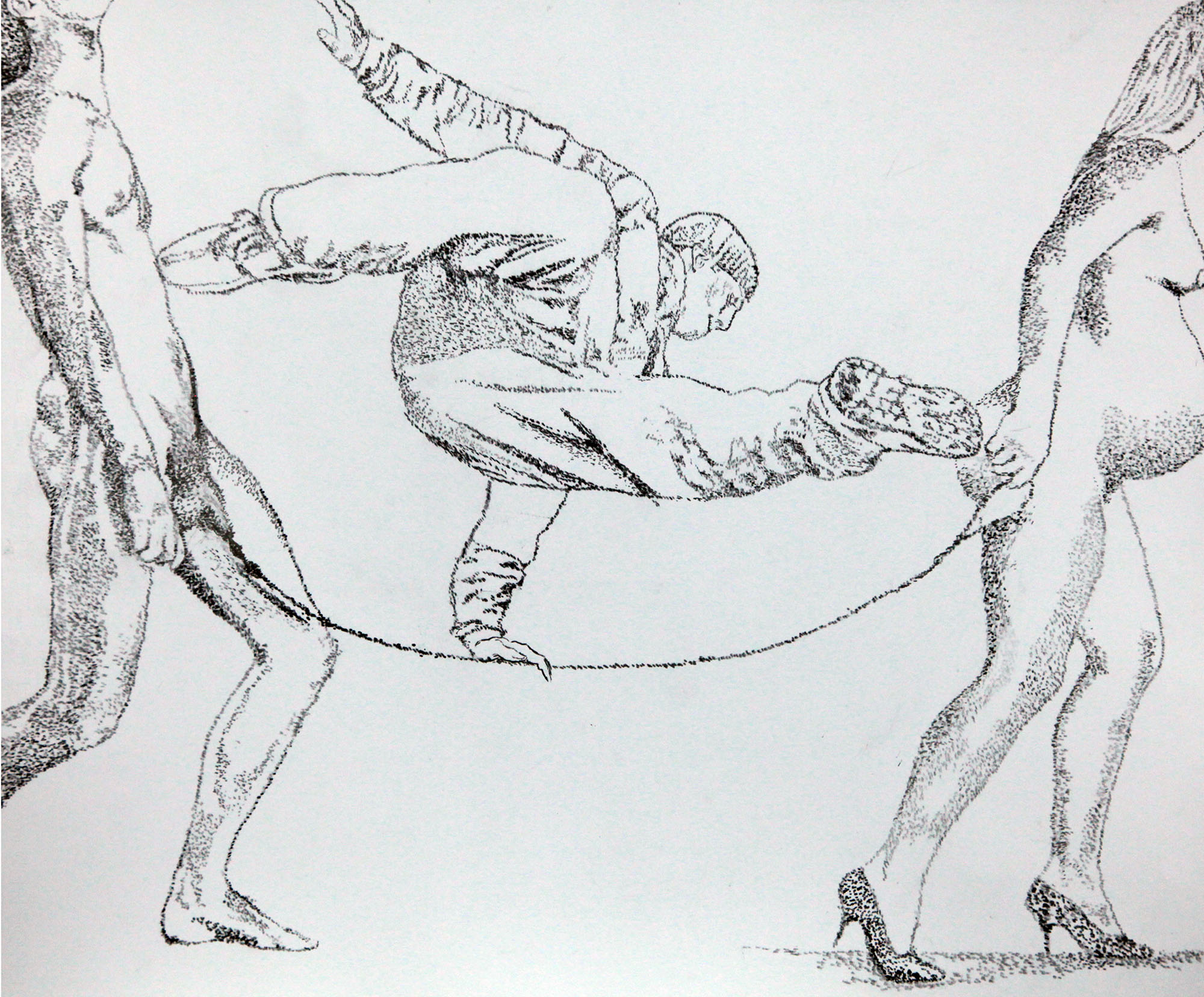

D.Y.: Since you are very active in international art circles you rarely have solo exhibitions in Turkey. I am sure lots of new works accumulate during this time, dozens of works that you haven’t had a chance to show in Turkey due to difficulties of opening solo exhibitions here. Let’s talk about the works in this exhibition now. We focused on your video piece “Remains of the Day” from 2013 and your two dimensional work in photography, drawing and water colours you made at different times. Your drawings are based on irony, anti-militarist references, socio-political and cultural paradigms. While the main sources of your videos and photographs are the city and the streets, your drawings and watercolours are predominantly based on metaphors, pastiches, surreal and absurd scenes. The video has a cinematographic language created through sequences ruled by an imaginary rhetoric. How do these different techniques connect to each other? What kind of processes do they go through to reach a conclusion? And in what way do they relate to the title “Curious Moments”?

F.Ö.: “Curious” was initially used by Şener Özmen. It was the title of a text he wrote about my work and it matched what I wanted to do in general. The fact that I am continuously producing could also be a disadvantage. The art world has some funny rules. It is as if a work needs to be shown right after it is been made in order for it to be considered new. They are considered to become old in a few years. Of course this is unacceptable. The rush to show works right after they have been made serves no purpose other than creating an “agenda”. To the contrary, if a work still makes an impact when presented some time after being produced it means it stands on solid ground. For that reason I am never rushing to make a solo exhibition. As you know the works in this exhibition were made in the last 4-5 years. Both my video works and photographs are based on performative fictions which is actually an element in all my works. The source of these fictions is again the city. When I am working on a drawing or watercolor, I approach it as if I am designing a stage performance. In that sense I see all my drawings as works that could be transformed into a performance or a sculpture. The images on my works on paper are not images falling from the sky. They don’t exist in a vacuum. To the contrary, the city or in more general terms the outside world is the source of newspapers, magazines, photographs from second hand shops, and any discarded and found materials I use. Naturally I can’t create any image unless I go out. Following this approach, the video “Remains of the Day” was also designed as a performative enactment of some of my works on paper. It is a complex combination of a series of stories that continuously unravel, disentangle and merge again. Just like a dream. It is the nature of a dream to have real and surreal situations occurring at the same time. The same actors appear throughout the film, but their experiences in life keep changing.

Hence, it was a good decision to describe such co-existence as “Curious Moments”, it made great sense. In works on paper we always encounter situations that don’t go right. By placing different images on top of each other or side by side, I try to create a bundle of metaphors that are weird, not fully comprehendible, open for interpretation and that cannot be tied to a fixed meaning. My conscious mind is at work at this stage. However, if I am to talk about a specific meaning in each work, it would mean I am on the wrong track. It is important not to mix things up. Explaining the emergence of a work of art or a project is not the same as determining the possible meanings the audience will get from the work in advance. The latter concept closes the work down.

D.Y.: “Remains of the Day” can be described as a performative video. In that sense it is a moving version of the pastiche-collage method in your works on paper. In my opinion it also has a refined manoeuvrability in bringing together concepts that look contradictory or function in different ways.

F.Ö.: I can explain the process further. My main concern is to explore the possibilities of a pluralistic discourse that would emerge through the coming together of different images. While I was making my painting series “Land” in the 1990s, I was tearing my drawings and works in ink on paper to pieces and sprinkling them on canvas. Then I would fix this messy group of pieces of paper on the surface with glue. The images which were initially realistic and recognizable would gain a half-real look through this process of fragmentation. Years later, I implemented a similar fragmentation and reassembling process in “Remains of the Day”.

D.Y.: Your work keeps a certain distance as a witness and in most of your works you are in the position of a recorder of memory. Apart from women’s issues, you also have works that examine issues about subculture, urban transformation, immigration and integration of unrecorded labour in the city economy. Your videos such as “We Speak Through the Sound of Junks”, “Today is Sun/Monday”, “Marble Dance”, “Embrace” and “I Can Sing” are also along those lines. When I saw the works you produced while you were an artist-in-residence at Cite des Arts in Paris in 2012, I again thought about the triangle between city-labour-creative economies. You also had participatory, collaborative projects that you made with street painters and performers. Could you please talk about those a bit?

F.Ö.: Such residency programs offer me periods of fully immersing myself into working and producing new work. I spend most of the day researching and working. During such times, I feel the responsibility of a student who needs to do his homework! The first work I did in Paris at Cite des Arts was “Hypocritical/Two Faced Bargain”. For many days I walked on the streets and searched for subject matters and materials trying to find out what I could do in that city. I was interested in the drawing techniques of the famous Paris street painters and their methods of portraying strangers they see for the first time in their lives. I was particularly curious about what kind of an attitude they have while making drawings on the street rather than in a studio. Then I started to think about strategies that would subvert their drawing habits and push them in other directions. They would draw a portrait of a person for 20 euros. Instead of having my portrait drawn by a single artist, I suggested two artists to make two portraits of me at the same time. However there was one condition: One of them would draw the left side of my face, and the other one would draw the right side, and I would pay them 10 euros, half of the money they would normally ask for. As a result I would get two self-portraits at the same time. But this would be a “Hypocritical/Two Faced negotiation”. That is how I named the work!

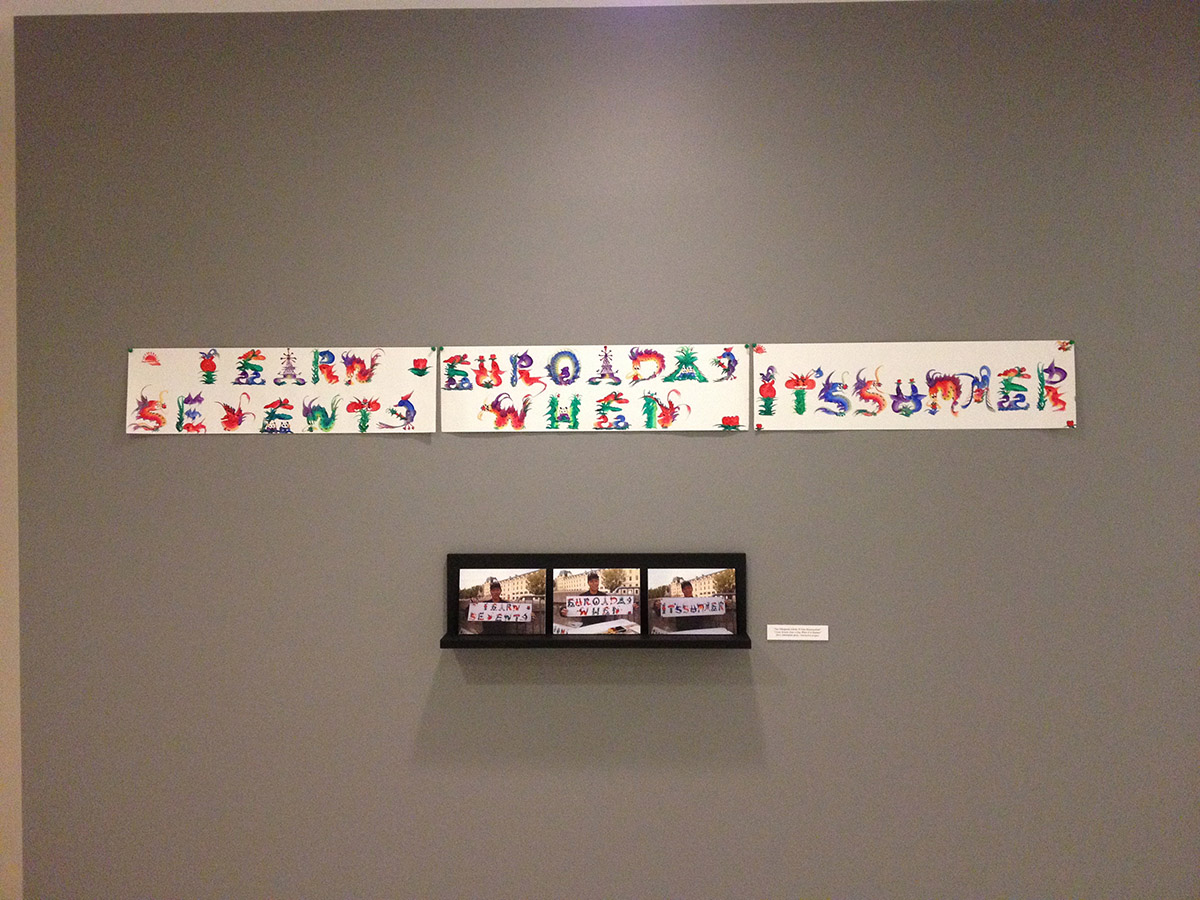

Another day, I met a Guinean immigrant who was doing various acrobatic movements with a football. I paid him 10 euros and asked him to climb up an electricity pole and hold the ball on one of his feet. Another street performer called Peter was acting a live sculpture on the street. In return for a reasonable fee I took him from his site of performance and placed him by the bank of Seine River. I asked him to stand as if he were a street cleaner who was sweeping all the money he earned during the day into the river. I photographed him in that position. Another project was developed through my engagement with a Chinese calligrapher who writes people’s names calligraphically onto sheets of paper in return for a certain fee. I asked him how much money he made in a day. He said, “70 euros since it is summer”. I said to him, “OK then! I will pay your rate, but instead of writing my name, you will write the sentence “I earn 70 euros since it is summer”. My intention was to make him do the calligraphy of his own earnings and return the issue to himself. In this way I was establishing some sort of an employee-employer relationship with the street performers and being part of the unrecorded economy. Apart from the economy of tourism in the city and the precariousness of labor in this market, I intended to point at the “art market” and the ambiguous struggle of the artist in this “market”, because cities shape us.

D.Y.: Yes, cities shape us. As Lefebvre says, everyday life offers us very important clues for understanding a society and the urban context is an actual “space” where these clues can be found. The horrendous craze for “transformation” of cities and the constant push for real estate with advertisements, magazine pages and newspaper inserts… A process that clears off the fragmented heterogeneous structure of cities in order to build homogenous cities that are more easily watched and easily controlled, just like what is happening in Istanbul and many other cities. Your works highlight a concern to keep real stories of this structure in the collective memory and to portray the places they take place in everyday life. In that sense you have a socio-critical attitude. This approach is evident in your video piece “We are the builders!” (2013).

F.Ö.: “We are the builders!” is a video dealing with urban issues and it has connections with my photographic works but this time from an external perspective. I spent one week with builders during a renovation and restoration project of a four storey apartment building. My intention was to make a documentary video about the exploitation of cheap labor intermixed with stories from their personal lives. A renovated four storey building appears at the end of the video but the stories behind the renovation of this small building have many more layers. That was what I wanted to show.

Art also has the function to draw attention to things which is the intention behind works that are described as political or socio-critical. I look at these works as oral history. Art does not need to be public in order to relate to life. In the case of public art, the necessity to establish a relation between art and life is due to the simultaneous referencing of the notions of “inside” and “outside”. It’s because the artistic materialization of the domestic codes, private and intimate stories, testimonies and personal experiences is another way of making things public. For example the video “Women in Love” works like this. It is based on intimate stories of women whose memories become public within a domestic space thereby functioning as oral history,.

D.Y.: “Women in Love” (2013) connects to another piece “Metamorphosis Chat” (2009) through their common concerns about womanhood and the modernization process.

F.Ö.: Yes, there is a relation between “Women in Love” and “Metamorphosis Chat” in terms of an engagement with women’s issues. In “Women in Love” we witness three women chatting: half fictional, half improvisational. They make confessions. Two of them reveal their feelings and thoughts about their late husbands, sometimes in a gossiping mode, sometimes as if reminiscing about old times. We witness a state of womanhood we are familiar with in Turkey. The pressure of traditions on women, violence from men, lives spent in lots of difficulties and unfair treatments. On the other hand, we also see the dilemmas of these women. For instance, the woman who complains about her husband’s beating and bullying shouts out her love and devotion to him despite everything. She wishes that her late husband were with her anyway. For me this is some sort of a prototype that represents personal dramas of women living in rural and suburban areas.

D.Y.: For me the dilemmas of these women are due to a shared and uneasy ground. It is related to the fact that they (are forced to) get married at a very young age. They have very limited opportunities to get to know themselves and to make their own wills and wishes a reality. Sometimes any such possibility is taken away from them completely. The women express their discontent with these male figures such as father, husband, son, whilst also approving of them at the same time. A conflict is at stake between the internalization of forced situations and a repressed resistance against them.

F.Ö.: One of the women in the video is Hediye. When her husband died, she put her son in his place. The son is in charge of the house now. She talks about the tortures of her husband in the past but she doesn’t know any other alternative to that. She transfers the male power from her late husband to her son. She is aware that there is something wrong with all this, but she can’t get rid of the effects of the internalization of these power relations that are also enforced through the society. Another thing is, she has been a victim of domestic violence but despite everything she can still say “Never mind, one way or another he was my man who stood by me, I wish he was still with me.” This of a husband who is no longer alive and who had inflicted physical violence against her. She becomes so weak that she can’t question the patriarchal power. The video shows the ironical and heartbreaking testimony of those women who do not question and break this vicious circle.

D.Y.: You are one of the rare male artists who address women’s issues. You don’t deal with a woman’s body as an aesthetic form or an object to look at. You don’t transform it into passive aesthetic structures. On the contrary, you engage with women’s issues as social phenomena with a realistic eye.

F.Ö.: My involvement in women’s issues started naturally, perhaps due to my autobiography. The Altındağ region of my childhood had a population of women who were both victims and strong characters. Earlier we talked about the slum culture. The woman was the figure who did the housekeeping and looked after, protected, managed and sustained the family. She struggled but was often a dominant, persevering and strong character at the same time. She was a lonely warrior within a patriarchal tradition fighting with the problems that her man was constantly creating (violence, insult, alcoholism, infidelity, etc.). Altındağ was, in effect, a microcosm of Turkey; it was reflecting the bigger picture of our society. Hence, naturally, through the years “women” became an issue that I engaged with - both autobiographically or intuitionally. It has always been of great importance to me.

D.Y.: Nonetheless, your artistic practice is not limited to certain concepts or subject matters, but it is distinguished with a diversity of contents and forms, which is also evident in “Curious Moments”. This exhibition does not present Ferhat Özgür’s oeuvre in its totality, but I believe it is a modest and profound exhibition that will remain in the minds of the audience for a long time.

April 2014, Istanbul

Derya Yücel: Your personal memory is often at the forefront of your work in which you address cultural phenomena such as borders and crossovers between centres and peripheries, immigration, religion, identity and the city. At the same time, you have always kept your refined approach in sharing your personal testimonies with the audience. “Curious Moments”, which is your first solo show in Turkey since 2008, offers an overview of the approaches central to your practice and the relations you establish between various media. In order to provide some background information I would like to start our conversation with some biographical details about you.

Ferhat Özgür: I was born in Ankara, where I also had my academic education. After graduating from Gazi University, Faculty of Education, Painting Department in 1989, I received my MA degree from Hacettepe University, Faculty of Fine Arts, Painting Department. I worked at Hacettepe University as a lecturer between 1993 and 2010, after which I moved to Istanbul. I spent most of my childhood and early youth around Altındağ, the district around Ankara Castle. That was a real slum area where mostly immigrants from central Anatolia settled and lived in extreme poverty. But I tend to refrain from such references as they could be incriminatory. I would say that, in general, I had a happy childhood. Regarding family relations, I have no childhood traumas that still haunt me. I had no oppression in my family, neither from my mother, nor my father who passed away at an early age, nor my siblings. But it is necessary to highlight the political and cultural climate of Altındağ, because it was a significant factor in my decision to study art and for me to identify what I am capable of. Interestingly, the street we lived in was in a strategic position. To the right side there was the Great Ankara Hospital, a place where German professors used to work in the 1930s, and its building had influences of German architecture. On the left side of the street, there was the Ulucanlar Half-Open Prison. I was about to start primary school when Yusuf Aslan, Deniz Gezmiş and Hüseyin İnan were executed there in 1972. Whilst playing on the streets, we would come across prisoners escaping from the prison and badly wounded patients coming to the hospital, both at the same time. It was almost like going back and forth between life and fiction. The older guys in an adjacent neighborhood were advocates of the rightwing/nationalist front while the nearer Aktaş quarter was leaning towards the left. Our neighbourhood Altındağ, being the middle region between the two, was one of the most volatile places in the 1970s when the conflict between right and left was most violent.

D.Y.: I know that growing up in these conditions has affected the way you formulated your artistic approach and your early works. While you were moving towards a certain direction in terms of content, you also experimented with different materials which heralded the variety of media in your later works. These could be considered as emerging points in your practice. Could you please talk about the effects of this period and environment on your artistic identity and the content and formal aspects of your work?

F.Ö.: In my childhood there was only one television channel. A cowboy film (“spaghetti western”) was shown every Sunday. For me and my friends in the neighborhood Sunday was the most exciting day! After watching these films we would go out immediately onto the streets and imitate the film, pretending to be cowboys! Most often I would take the role of an American Indian. Such a motive to imitate films must have not only offered me a way to experience life and fiction at the same time but also increased my interest in cinema. When eventually I decided to make art as a full-time profession, the Altındağ-Ulucanlar area formed the main ground for my works both in terms of content and form.

For example, during my educational years at the beginning of the 1990s, Zahit Büyükişliyen, my workshop professor at Hacettepe, had given an assignment to make a site-specific installation project. Such work was not common in Turkey in those years. As a prospective artist, who had never left Ankara and whose only experience of seeing art was limited to State Painting and Sculpture Museum exhibitions, competition exhibitions such as those organized by DYO (a private paint company), and a few artist books, I got really excited about this idea of a “site-specific” work. As I was living in a single roomed shanty (gecekondu) house and inspired by Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, I transformed my room into “The Room of a Young Poet” i.e. thousands of cigarette butts on the floor, scattered pieces of crumpled paper with scribbles and notes, books all around the place, a desk with a typewriter and a tea glass on it, etc. It was as if a young poet was trying hard to write a poem but he was not satisfied and he tore apart everything he wrote, throwing around the pieces of paper. He was in the throes of creation. We weren’t so well-aware of things then, so I don’t have any photograph of the space or layout of the work. I had shown the work to my professor at home as well. In those years, I had also seen a fascinating solo exhibition of Claude Viallat, one of the most important members of the “Support-Surface” movement, at Ankara State Painting and Sculpture Museum. That exhibition was a breaking point for me. I gained courage in a sense.

D.Y.: What kind of courage are you talking about? I will again ask you to relate this question to the influence of your living conditions on your art practice.

F.Ö.: Viallat had given up on framing and he was making meters long transportable paintings. The space I was living in was about 4-5 square meters altogether. I also wanted to play with large scale color marks and almost exhausted myself experimenting with things. I have so many beautiful memories of the following period: My mother would boil powder fabric paints in large boilers and I would get large pieces of fabrics from tent shops and scrap dealers in Ulus and plunge them into these boilers to give them color. And then I would play with the motifs and get random images by decoloring them with ozone. I could iron and fold these large size fabrics, store them in plastic bags and carry them over to wherever I wanted. The works were nomadic in a sense. At some point my friends said, “Oh, he is imitating Viallat,” but I was proud of that. I thought everyone should have a master.

D.Y.: And a source of inspiration. Your realistic and emotional connection with the neighbourhood you used to live in has been a source of inspiration to you for a long time. Kathryn Rhomberg, the curator of the 6th Berlin Biennial, described your photographic piece “Let Everyone Come Out Today” (2002) that you made on that street as “an oeuvre where all of your art works unite”. Again the same street was the leading role in this piece which you made in the years when you were moving towards photography and video! I think this piece has an insider’s view since you have inscribed this place in your memory, hence were able to engage with its reality as your own, as well as an outsider’s view that you created from a distance without exploiting the subject or being alienated.

F.Ö.: Yes, even after many years I was still frequently going to the street where I was born and grew up. My family was still living there. It was Sunday. I went there with my camera. I didn’t really tell anyone what to do. I knocked on the doors of all neighbors and I asked them to come outside because I knew that the street would not continue to exist and its residents would never come together in the same way again. “We will take a souvenir photo,” I said. I wanted them to experience a unique moment together. I lined them up along the street and photographed them both from the entrance and the exit of the street.

D.Y.: Since you are very active in international art circles you rarely have solo exhibitions in Turkey. I am sure lots of new works accumulate during this time, dozens of works that you haven’t had a chance to show in Turkey due to difficulties of opening solo exhibitions here. Let’s talk about the works in this exhibition now. We focused on your video piece “Remains of the Day” from 2013 and your two dimensional work in photography, drawing and water colours you made at different times. Your drawings are based on irony, anti-militarist references, socio-political and cultural paradigms. While the main sources of your videos and photographs are the city and the streets, your drawings and watercolours are predominantly based on metaphors, pastiches, surreal and absurd scenes. The video has a cinematographic language created through sequences ruled by an imaginary rhetoric. How do these different techniques connect to each other? What kind of processes do they go through to reach a conclusion? And in what way do they relate to the title “Curious Moments”?

F.Ö.: “Curious” was initially used by Şener Özmen. It was the title of a text he wrote about my work and it matched what I wanted to do in general. The fact that I am continuously producing could also be a disadvantage. The art world has some funny rules. It is as if a work needs to be shown right after it is been made in order for it to be considered new. They are considered to become old in a few years. Of course this is unacceptable. The rush to show works right after they have been made serves no purpose other than creating an “agenda”. To the contrary, if a work still makes an impact when presented some time after being produced it means it stands on solid ground. For that reason I am never rushing to make a solo exhibition. As you know the works in this exhibition were made in the last 4-5 years. Both my video works and photographs are based on performative fictions which is actually an element in all my works. The source of these fictions is again the city. When I am working on a drawing or watercolor, I approach it as if I am designing a stage performance. In that sense I see all my drawings as works that could be transformed into a performance or a sculpture. The images on my works on paper are not images falling from the sky. They don’t exist in a vacuum. To the contrary, the city or in more general terms the outside world is the source of newspapers, magazines, photographs from second hand shops, and any discarded and found materials I use. Naturally I can’t create any image unless I go out. Following this approach, the video “Remains of the Day” was also designed as a performative enactment of some of my works on paper. It is a complex combination of a series of stories that continuously unravel, disentangle and merge again. Just like a dream. It is the nature of a dream to have real and surreal situations occurring at the same time. The same actors appear throughout the film, but their experiences in life keep changing.

Hence, it was a good decision to describe such co-existence as “Curious Moments”, it made great sense. In works on paper we always encounter situations that don’t go right. By placing different images on top of each other or side by side, I try to create a bundle of metaphors that are weird, not fully comprehendible, open for interpretation and that cannot be tied to a fixed meaning. My conscious mind is at work at this stage. However, if I am to talk about a specific meaning in each work, it would mean I am on the wrong track. It is important not to mix things up. Explaining the emergence of a work of art or a project is not the same as determining the possible meanings the audience will get from the work in advance. The latter concept closes the work down.

D.Y.: “Remains of the Day” can be described as a performative video. In that sense it is a moving version of the pastiche-collage method in your works on paper. In my opinion it also has a refined manoeuvrability in bringing together concepts that look contradictory or function in different ways.

F.Ö.: I can explain the process further. My main concern is to explore the possibilities of a pluralistic discourse that would emerge through the coming together of different images. While I was making my painting series “Land” in the 1990s, I was tearing my drawings and works in ink on paper to pieces and sprinkling them on canvas. Then I would fix this messy group of pieces of paper on the surface with glue. The images which were initially realistic and recognizable would gain a half-real look through this process of fragmentation. Years later, I implemented a similar fragmentation and reassembling process in “Remains of the Day”.

D.Y.: Your work keeps a certain distance as a witness and in most of your works you are in the position of a recorder of memory. Apart from women’s issues, you also have works that examine issues about subculture, urban transformation, immigration and integration of unrecorded labour in the city economy. Your videos such as “We Speak Through the Sound of Junks”, “Today is Sun/Monday”, “Marble Dance”, “Embrace” and “I Can Sing” are also along those lines. When I saw the works you produced while you were an artist-in-residence at Cite des Arts in Paris in 2012, I again thought about the triangle between city-labour-creative economies. You also had participatory, collaborative projects that you made with street painters and performers. Could you please talk about those a bit?

F.Ö.: Such residency programs offer me periods of fully immersing myself into working and producing new work. I spend most of the day researching and working. During such times, I feel the responsibility of a student who needs to do his homework! The first work I did in Paris at Cite des Arts was “Hypocritical/Two Faced Bargain”. For many days I walked on the streets and searched for subject matters and materials trying to find out what I could do in that city. I was interested in the drawing techniques of the famous Paris street painters and their methods of portraying strangers they see for the first time in their lives. I was particularly curious about what kind of an attitude they have while making drawings on the street rather than in a studio. Then I started to think about strategies that would subvert their drawing habits and push them in other directions. They would draw a portrait of a person for 20 euros. Instead of having my portrait drawn by a single artist, I suggested two artists to make two portraits of me at the same time. However there was one condition: One of them would draw the left side of my face, and the other one would draw the right side, and I would pay them 10 euros, half of the money they would normally ask for. As a result I would get two self-portraits at the same time. But this would be a “Hypocritical/Two Faced negotiation”. That is how I named the work!

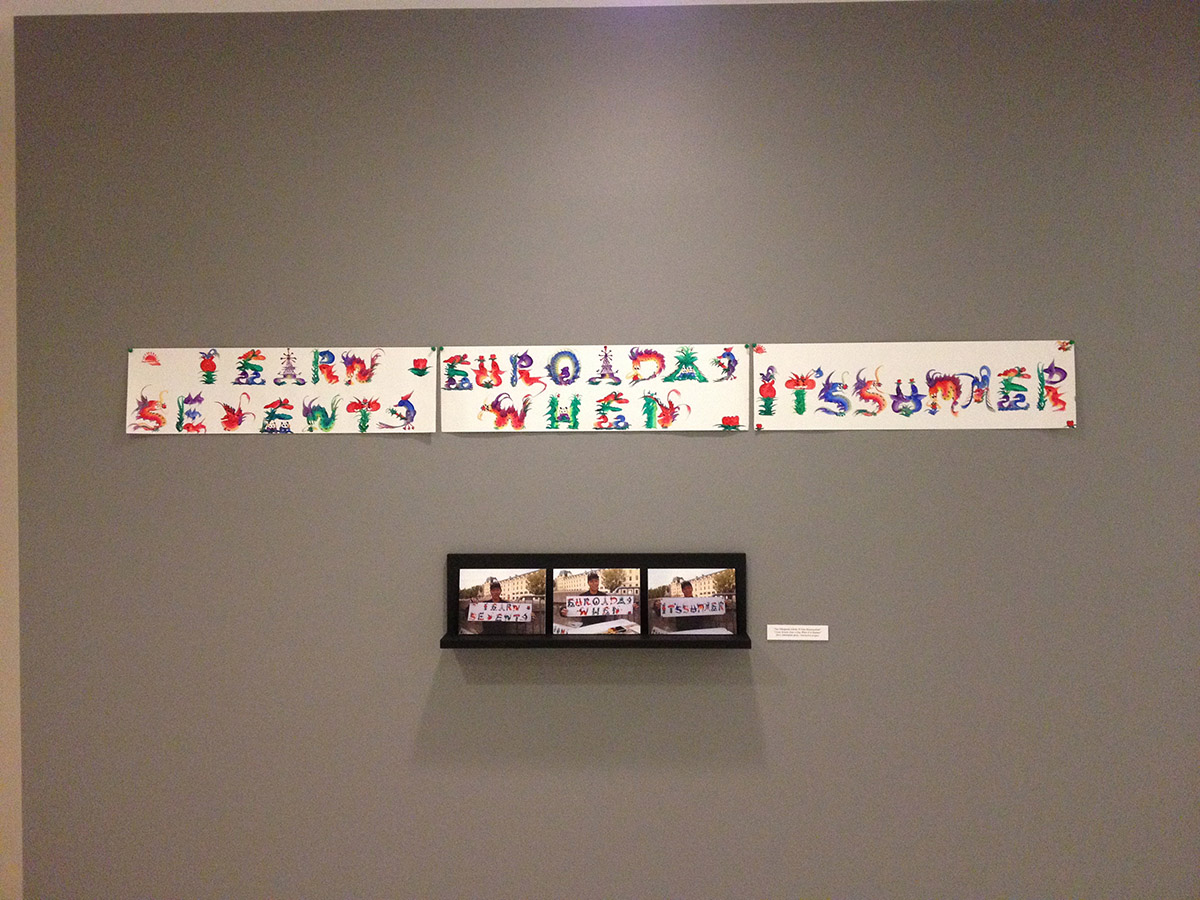

Another day, I met a Guinean immigrant who was doing various acrobatic movements with a football. I paid him 10 euros and asked him to climb up an electricity pole and hold the ball on one of his feet. Another street performer called Peter was acting a live sculpture on the street. In return for a reasonable fee I took him from his site of performance and placed him by the bank of Seine River. I asked him to stand as if he were a street cleaner who was sweeping all the money he earned during the day into the river. I photographed him in that position. Another project was developed through my engagement with a Chinese calligrapher who writes people’s names calligraphically onto sheets of paper in return for a certain fee. I asked him how much money he made in a day. He said, “70 euros since it is summer”. I said to him, “OK then! I will pay your rate, but instead of writing my name, you will write the sentence “I earn 70 euros since it is summer”. My intention was to make him do the calligraphy of his own earnings and return the issue to himself. In this way I was establishing some sort of an employee-employer relationship with the street performers and being part of the unrecorded economy. Apart from the economy of tourism in the city and the precariousness of labor in this market, I intended to point at the “art market” and the ambiguous struggle of the artist in this “market”, because cities shape us.

D.Y.: Yes, cities shape us. As Lefebvre says, everyday life offers us very important clues for understanding a society and the urban context is an actual “space” where these clues can be found. The horrendous craze for “transformation” of cities and the constant push for real estate with advertisements, magazine pages and newspaper inserts… A process that clears off the fragmented heterogeneous structure of cities in order to build homogenous cities that are more easily watched and easily controlled, just like what is happening in Istanbul and many other cities. Your works highlight a concern to keep real stories of this structure in the collective memory and to portray the places they take place in everyday life. In that sense you have a socio-critical attitude. This approach is evident in your video piece “We are the builders!” (2013).

F.Ö.: “We are the builders!” is a video dealing with urban issues and it has connections with my photographic works but this time from an external perspective. I spent one week with builders during a renovation and restoration project of a four storey apartment building. My intention was to make a documentary video about the exploitation of cheap labor intermixed with stories from their personal lives. A renovated four storey building appears at the end of the video but the stories behind the renovation of this small building have many more layers. That was what I wanted to show.

Art also has the function to draw attention to things which is the intention behind works that are described as political or socio-critical. I look at these works as oral history. Art does not need to be public in order to relate to life. In the case of public art, the necessity to establish a relation between art and life is due to the simultaneous referencing of the notions of “inside” and “outside”. It’s because the artistic materialization of the domestic codes, private and intimate stories, testimonies and personal experiences is another way of making things public. For example the video “Women in Love” works like this. It is based on intimate stories of women whose memories become public within a domestic space thereby functioning as oral history,.

D.Y.: “Women in Love” (2013) connects to another piece “Metamorphosis Chat” (2009) through their common concerns about womanhood and the modernization process.

F.Ö.: Yes, there is a relation between “Women in Love” and “Metamorphosis Chat” in terms of an engagement with women’s issues. In “Women in Love” we witness three women chatting: half fictional, half improvisational. They make confessions. Two of them reveal their feelings and thoughts about their late husbands, sometimes in a gossiping mode, sometimes as if reminiscing about old times. We witness a state of womanhood we are familiar with in Turkey. The pressure of traditions on women, violence from men, lives spent in lots of difficulties and unfair treatments. On the other hand, we also see the dilemmas of these women. For instance, the woman who complains about her husband’s beating and bullying shouts out her love and devotion to him despite everything. She wishes that her late husband were with her anyway. For me this is some sort of a prototype that represents personal dramas of women living in rural and suburban areas.

D.Y.: For me the dilemmas of these women are due to a shared and uneasy ground. It is related to the fact that they (are forced to) get married at a very young age. They have very limited opportunities to get to know themselves and to make their own wills and wishes a reality. Sometimes any such possibility is taken away from them completely. The women express their discontent with these male figures such as father, husband, son, whilst also approving of them at the same time. A conflict is at stake between the internalization of forced situations and a repressed resistance against them.

F.Ö.: One of the women in the video is Hediye. When her husband died, she put her son in his place. The son is in charge of the house now. She talks about the tortures of her husband in the past but she doesn’t know any other alternative to that. She transfers the male power from her late husband to her son. She is aware that there is something wrong with all this, but she can’t get rid of the effects of the internalization of these power relations that are also enforced through the society. Another thing is, she has been a victim of domestic violence but despite everything she can still say “Never mind, one way or another he was my man who stood by me, I wish he was still with me.” This of a husband who is no longer alive and who had inflicted physical violence against her. She becomes so weak that she can’t question the patriarchal power. The video shows the ironical and heartbreaking testimony of those women who do not question and break this vicious circle.

D.Y.: You are one of the rare male artists who address women’s issues. You don’t deal with a woman’s body as an aesthetic form or an object to look at. You don’t transform it into passive aesthetic structures. On the contrary, you engage with women’s issues as social phenomena with a realistic eye.

F.Ö.: My involvement in women’s issues started naturally, perhaps due to my autobiography. The Altındağ region of my childhood had a population of women who were both victims and strong characters. Earlier we talked about the slum culture. The woman was the figure who did the housekeeping and looked after, protected, managed and sustained the family. She struggled but was often a dominant, persevering and strong character at the same time. She was a lonely warrior within a patriarchal tradition fighting with the problems that her man was constantly creating (violence, insult, alcoholism, infidelity, etc.). Altındağ was, in effect, a microcosm of Turkey; it was reflecting the bigger picture of our society. Hence, naturally, through the years “women” became an issue that I engaged with - both autobiographically or intuitionally. It has always been of great importance to me.

D.Y.: Nonetheless, your artistic practice is not limited to certain concepts or subject matters, but it is distinguished with a diversity of contents and forms, which is also evident in “Curious Moments”. This exhibition does not present Ferhat Özgür’s oeuvre in its totality, but I believe it is a modest and profound exhibition that will remain in the minds of the audience for a long time.