MURAT MOROVA & DERYA YÜCEL

December 2015, Istanbul

In his art practice that he shapes in an expeditionary thought system, Murat Morova creates his own myth, positioned “between” Western and Eastern mythologies. Crossbreeding, therefore mutating traditional art aesthetics within the framework of contemporary concepts, he creates a visual iconography of his own. The conversation with the artist on his solo exhibition “RAVi”.

Derya Yücel: We actually gathered to speak about your latest works, and solo exhibition yet unfortunately the trauma of terror from last night’s horrible events in Paris are with us today. These traumas are getting heavier as they recur, while our senses of justice and conscience are being damaged, and the incurable wounds deepen with daily politics like social injustice, torture, pressure, labor exploitation, and terror. On the other side, the annihilation of the Earth is in process showing its signs with climate change as a result of humanity’s irresponsibility towards the Earth/Nature, global warming, depletion of resources/species, etc. Thinking of this, we know that the themes you have been treating in your extended practice have been shaped around this problematic. The exhibition at Galeri Nev is called “Ravi”. Can we say that Murat Morova is a modern “Ravi” narrating today’s stories using the past’s metaphors with the language of aesthetics? You may want to start with the story that originated this exhibition.

Murat Morova: I would like to start with the accumulation that led to this exhibition. There is a “romantic” side to the exhibited works in relation to my personal history. As a kid, my grandmother and my mother would always take me with them when they would go shopping. Üsküdar, where I was born, was, just as is today, a more traditional district in the 1950’s; you could feel the link to the past whether because of that neighborhood feeling, or its examples of traditional architecture. People would sell different materials and products on the counters in front of the mosques. Religious books as well as social books would be sold on the counters. Folktales, myths, epic books printed with lithography containing stories on the battles of Hazrat Ali, epics of Seyyid Battal Ghazi, Tahir and Zühre, Kerem and Aslı, etc. would all have one thing in common: they would have narrative pictures. We would definitely buy some of these books, and they would affect me a lot thanks to its colorful, and naïve pictures, even though I did not know how to read at the time. These stories would have their specific literary tone. I remember The Battles of Hazrat Ali the most among these books; this is because Hazrat Ali was a character free of his time, and his stories would have a simple present tense perspective, encompassing all times. In some stories, he would go through events, or encounter other historic figures that did not belong to his period; the heroisms and religious narratives would blend together. Bandits, jinni, fairies, dragons, superhuman entities would accompany these stories. But the ultimate gist was always about the human virtue, feelings of justice and mercy, consciousness and generosity. There is always a moral. Hazrat Ali, in the belief systematic that he represents, has always been described as a figure that had all the features of a mature, good-hearted person, almost a perfect human being. He is the Eastern version of the savior hero cult, prevalent in most Western stories. Yet, he is more of a hero outstanding with his humanistic features, rather than his Western equivalents’ physical superiorities; like more beautiful, bigger, stronger, well built and superhuman. Hazrat Ali’s physical features many times carries a fictional exaggeration since they were told within a tale or legend.

D. Y.: Yet your figures do not create a heroic myth. I perceive your modest yet rebellious figures in relation with your personal and artistic state of remaining in purgatory, also with your state of being both inside and outside around the sensibilities that you equip yourself with. In a world buried in inhuman, hegemonic, exploiter, tyrannizer systems, your “perfect human being” image carries a part of all of us, trying to move in his own circle(s) with demands for justice, rightness, consciousness. How strong can we be in breaking this circle, and fighting with the one outside? We sometimes feel obliged to draw our own circle(s) to be able to create our shelters. This can be valid on a personal or societal level or even in the art field. We keep seeking other heroes to be freed from the challenges of yesterday, today and tomorrow. How did you transmit the stories at this exhibition? How did you shape Ravi’s voice?

M. M.: A man’s hero is himself. The issue here is being able to get acquainted with our own circles, and show the will to either break or to draw them. Although these are matters of utmost importance and urgency, in this exhibition I tried to switch on very simple, almost childish, and naïve concepts. I looked for the purest, least engaged states of this attitude of being a “perfect human being”; the new human typology, treating today’s traumas and problems like yesterday’s malicious enemies and monsters, and dealing with today’s evil, without any great ideological engagements. There is a narrator, a storyteller in all of these folk tales printed by lithography. This person gives reference to the “Ravi”’s as a basis for what he narrates. Ravi is the one who relates, tells, and sources. Firstly, he is a figure who transmits, carries the sayings/deeds of the Prophet in Islam. Of course, not all carriers, or narrators can get this title; to be a Ravi is considered as a degree. In time, “ravi” lost its meaning in religious etymology, and was widely used amongst people to describe anyone who told legends. Yes, I acted as some sort of a “Ravi” when narrating this exhibition. Because, fundamentally, the subjects of these folk tales - the malicious events of the past, the feelings of justice, consciousness, and mercy suffering from erosion, ongoing cruelties and raids- share the same bloodline with subjects of today. Although different in shape, they are conceptually the same. Therefore, my “Ravi”ness, stems from me, presenting the stories of today, in the form of those days.

D. Y.: Your ties with traditional aesthetics do not only appear on a physical level. In fact, the priority of your medium selection emerges at the point where it supports the content. With this outturn, you end up producing a decided work as a result of a rigorous selection with the aim of visualizing the content, message or story that you want to deliver. Therefore, although the surface aesthetics’ taste, arising from Islamic or traditional forms, is heavily present, it is not very possible to limit your works within one medium. Painting, sculpture, tile, ready object-installation, photography, collage… The form is supporting your story. The same can be told of your works in this exhibition.

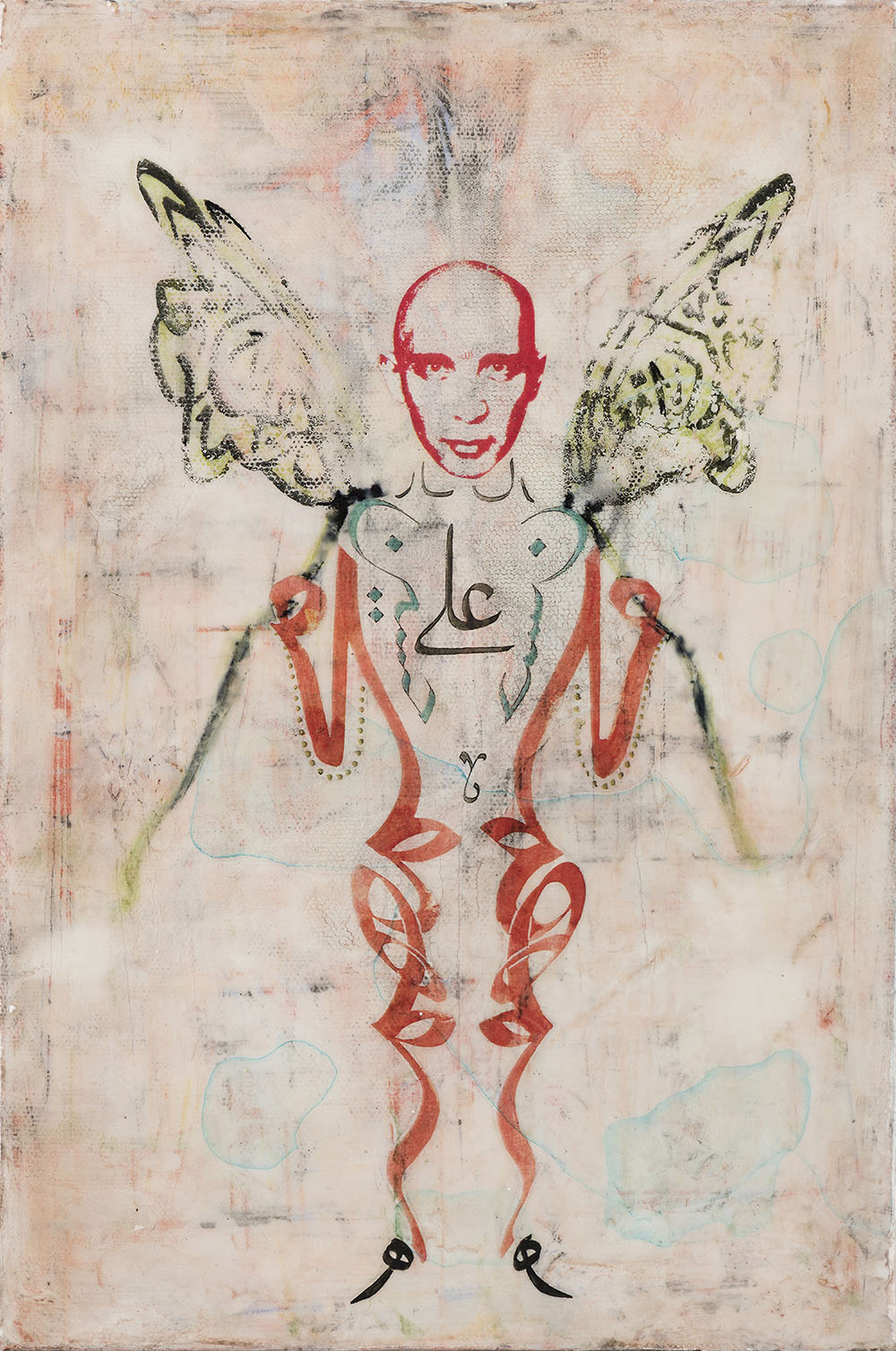

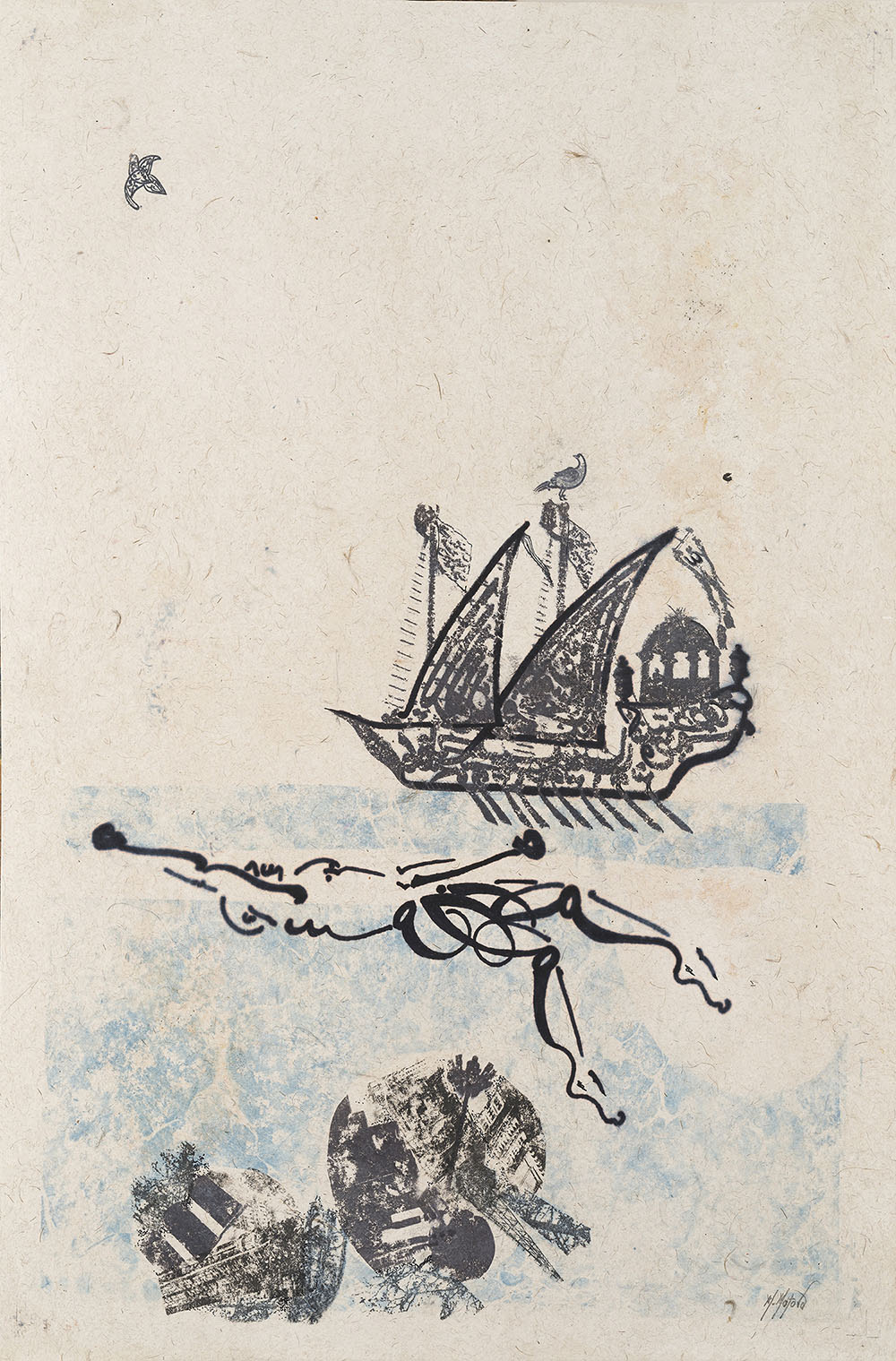

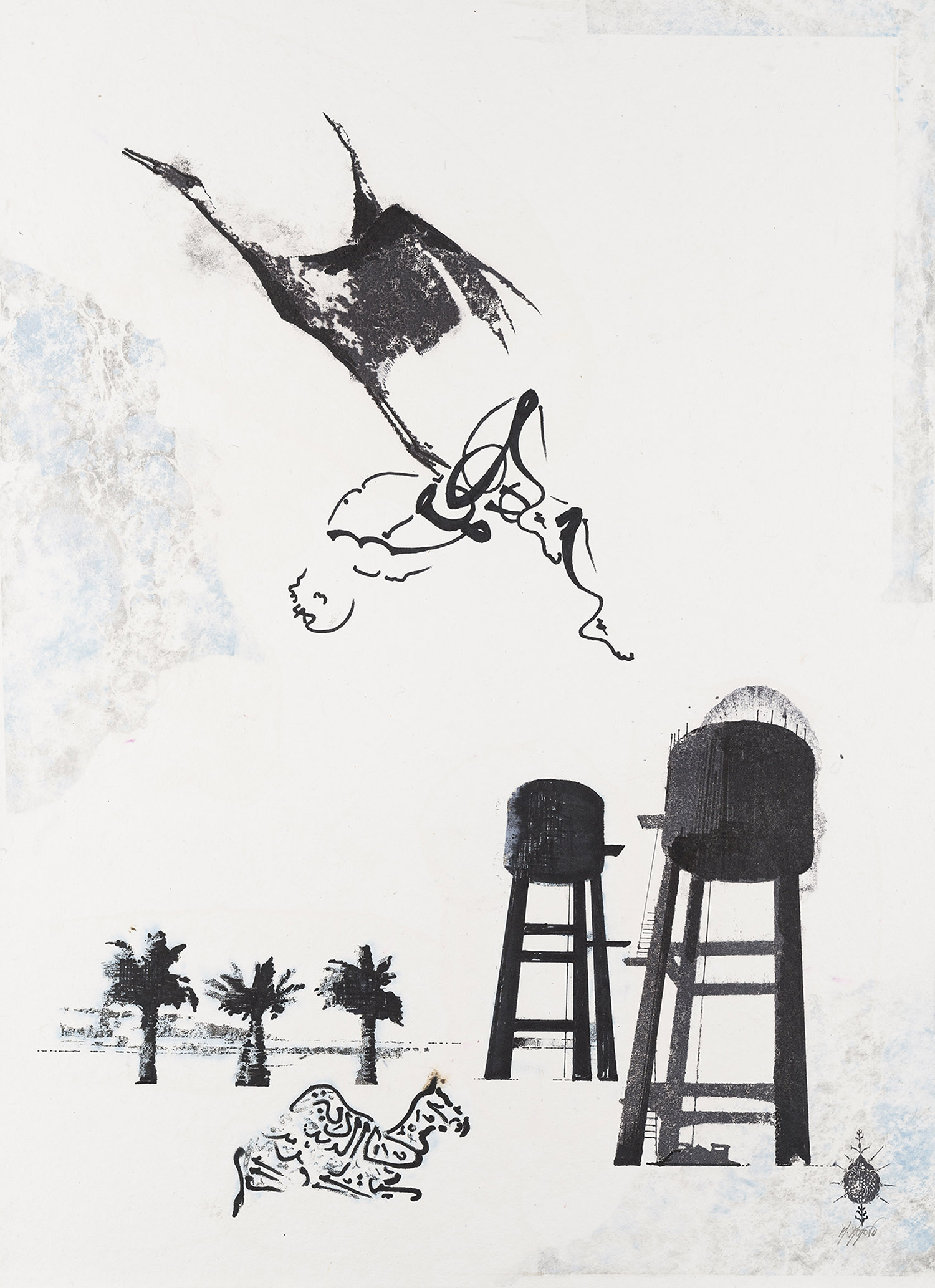

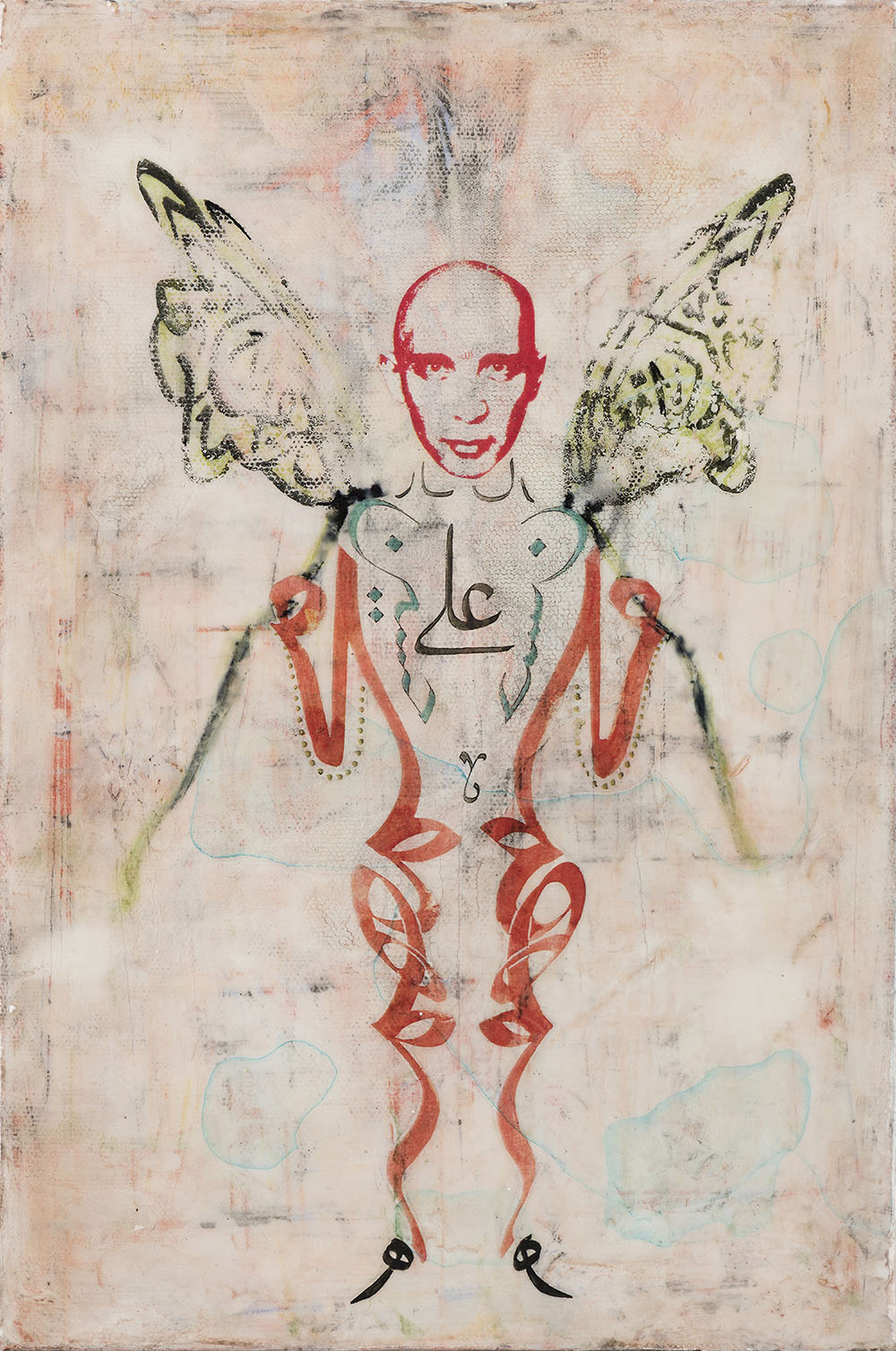

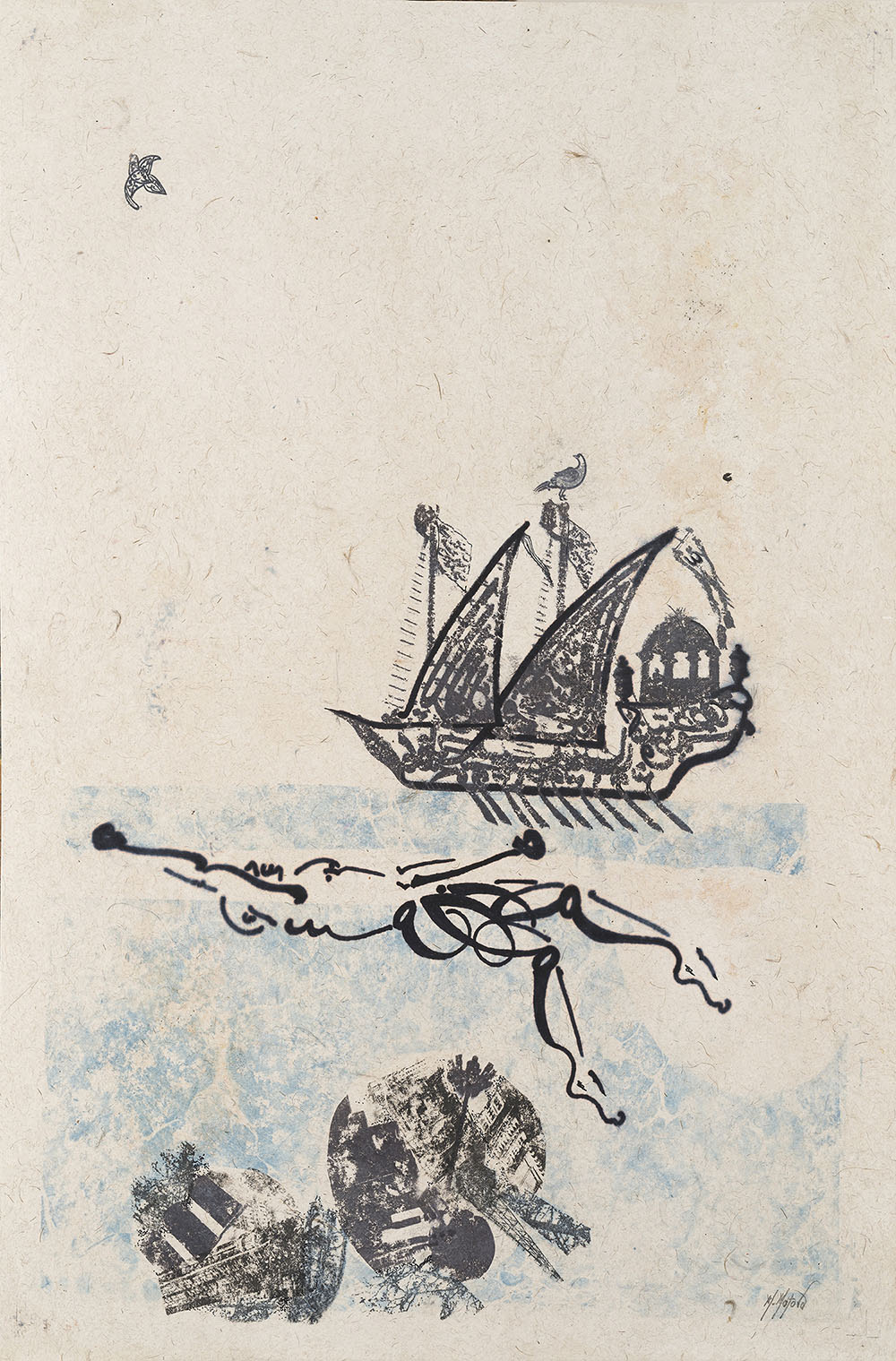

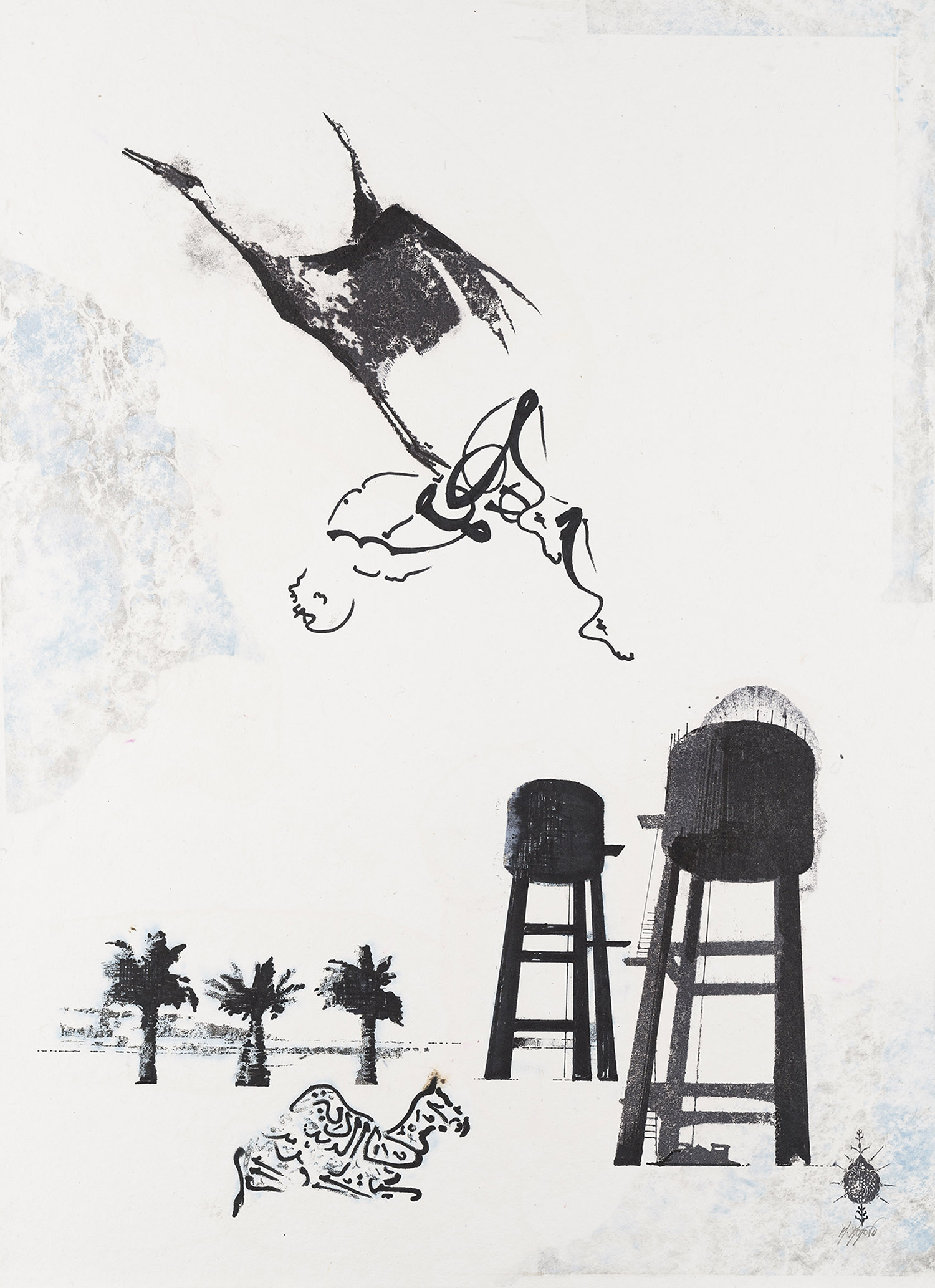

M. M.: While revealing the works at this exhibition, I had to think of the level of the material’s naivety, and not of the aesthetics produced via today’s technology. I wanted it to have a form that gives a reference to the past. I was careful that they had the same color harmony as in the folk tale books printed by lithography, or the same paper texture. Therefore, in the 12 works that draw the main axis of the series, I used watercolor, drawing ink, powder paint, and some ageing techniques on handmade paper. I applied a composition in flu shades where you could barely see images referencing traditional forms. Surface aesthetics is an attitude outstanding in my production. I wanted it to have an illustrative taste without being caricaturized. I paid attention to this because the narrator who tells an illustrative story using a certain aesthetical language, while is a tradition in Western painting; it also is an ongoing taste at us. We may call it Eastern aesthetics, since our visual heritage until our encounter with Western painting is predominantly on the book surfaces. Like miniature, visual representation is an entity mainly supporting the text, the story. I do not own a touching work method based on inspiration, or born out of sudden impulse. My connection with the text during the process of research, collecting, reading, thinking, maturing and unveiling is very strong. The relationship of the works at this exhibition with the text manifests itself via the materials they take reference from. Sometimes, I choose to make use of several various mediums together in a solo exhibition, but this time I especially avoided that. There are paper works and canvas almost manipulated to look like paper. I tried to bring out the fragmentally metamorphosed surfaces. This is how we ended up with the two series consisting of 14 pieces in total. I used my own semblance in one of the 3 smaller canvas works exhibited at the entrance. My face appears on the form of a perfect human being, and on a figure fluttering wings with his/her own power, struggling, battling frenetically towards an action, a discourse.

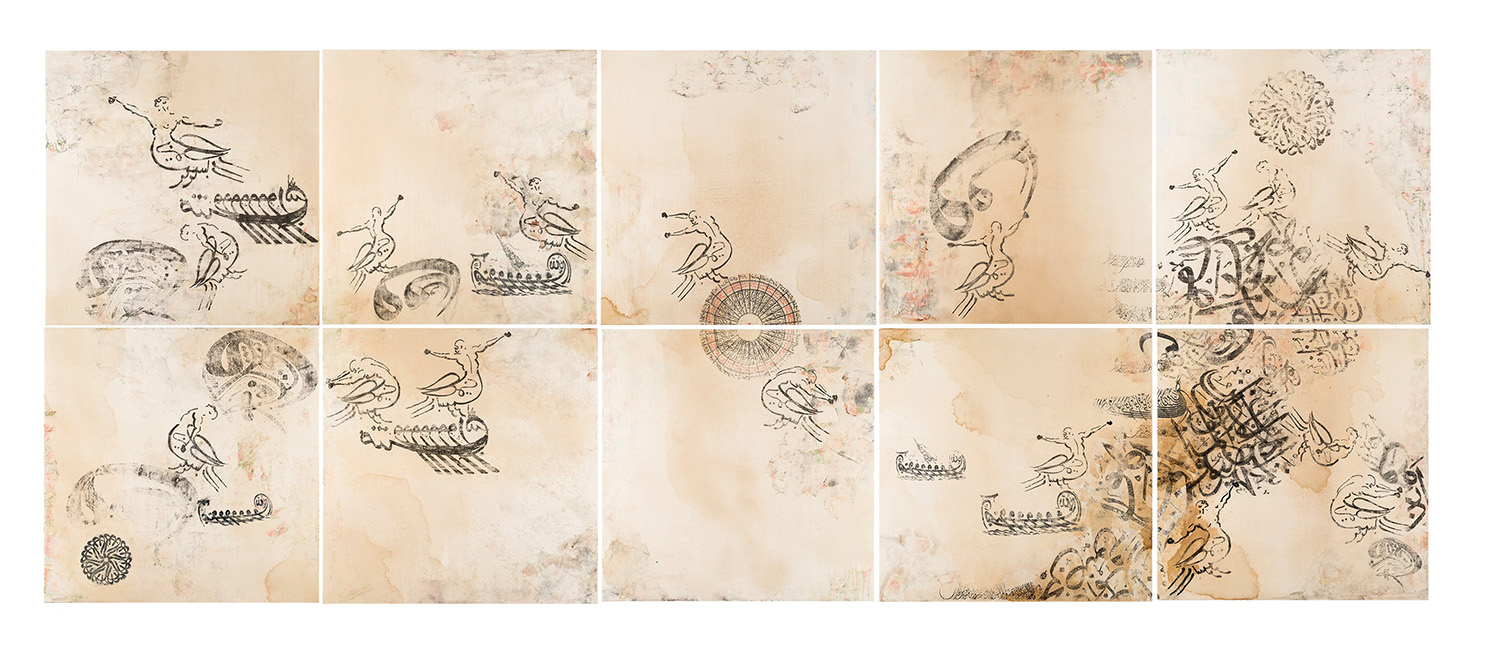

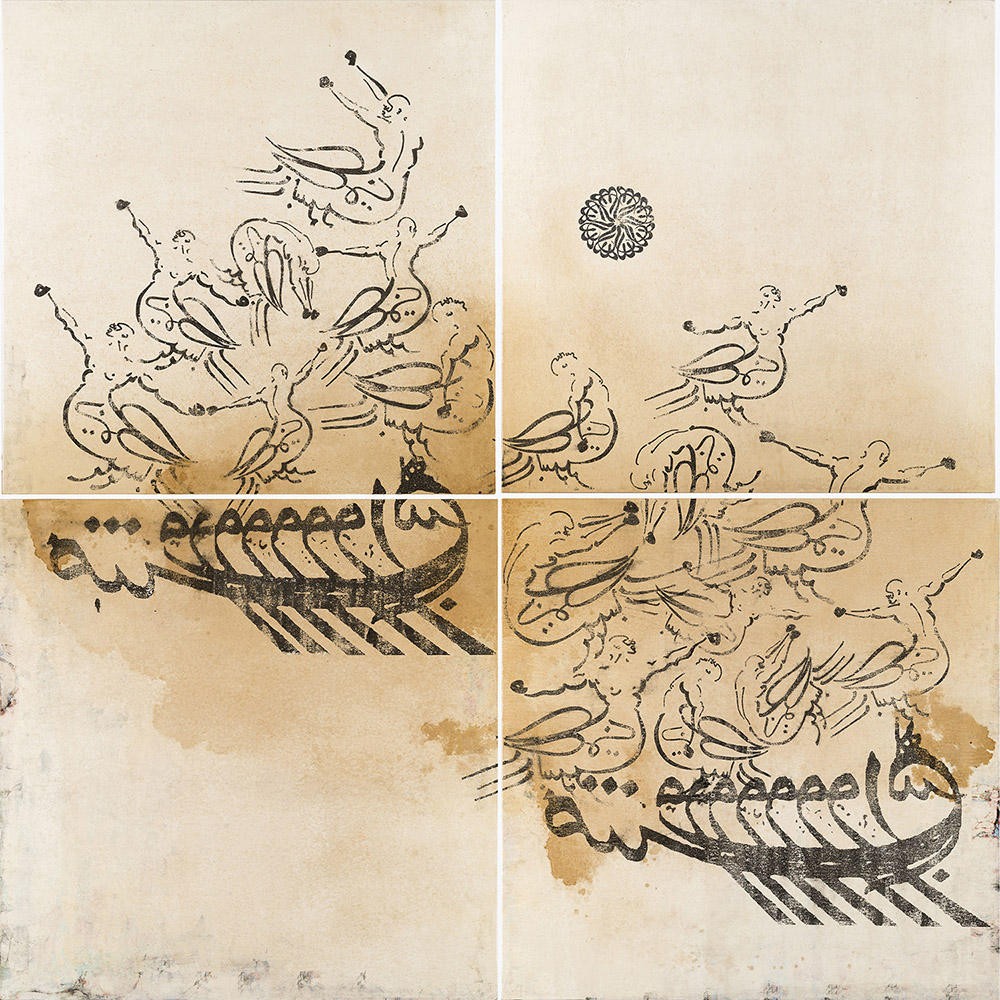

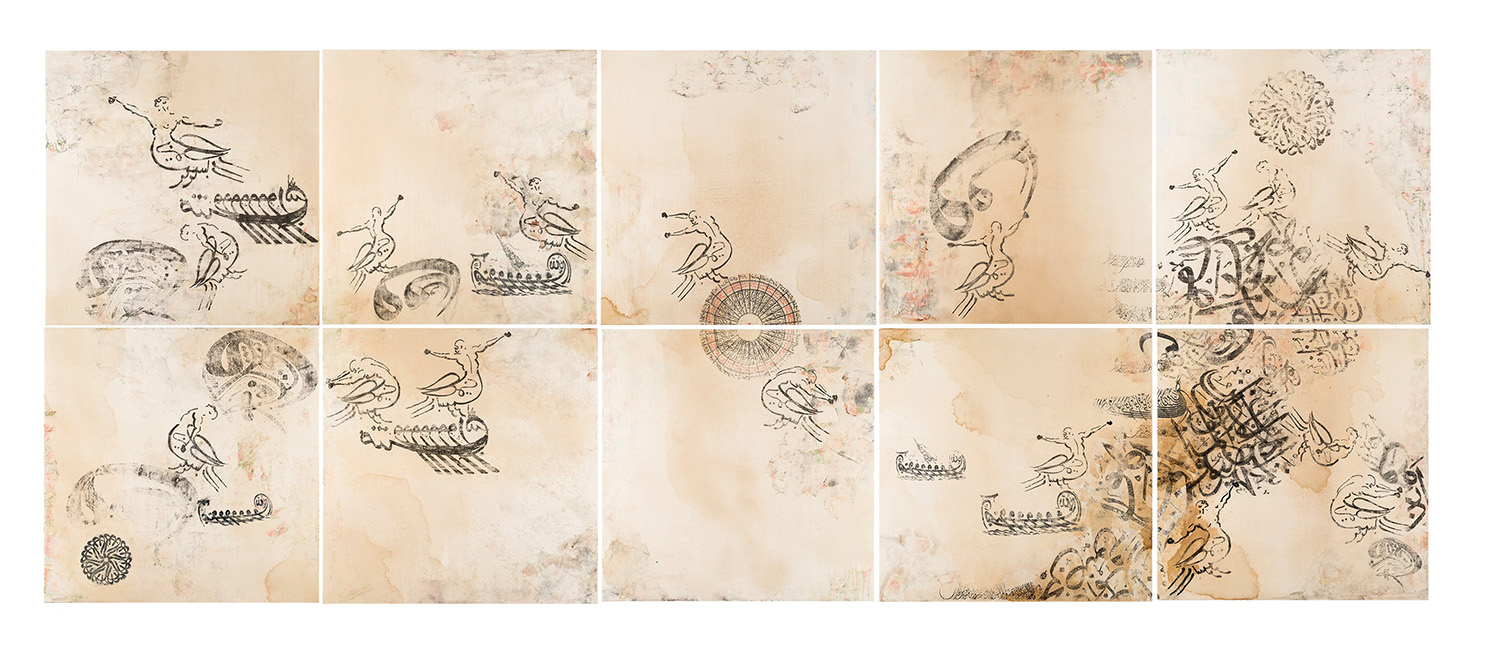

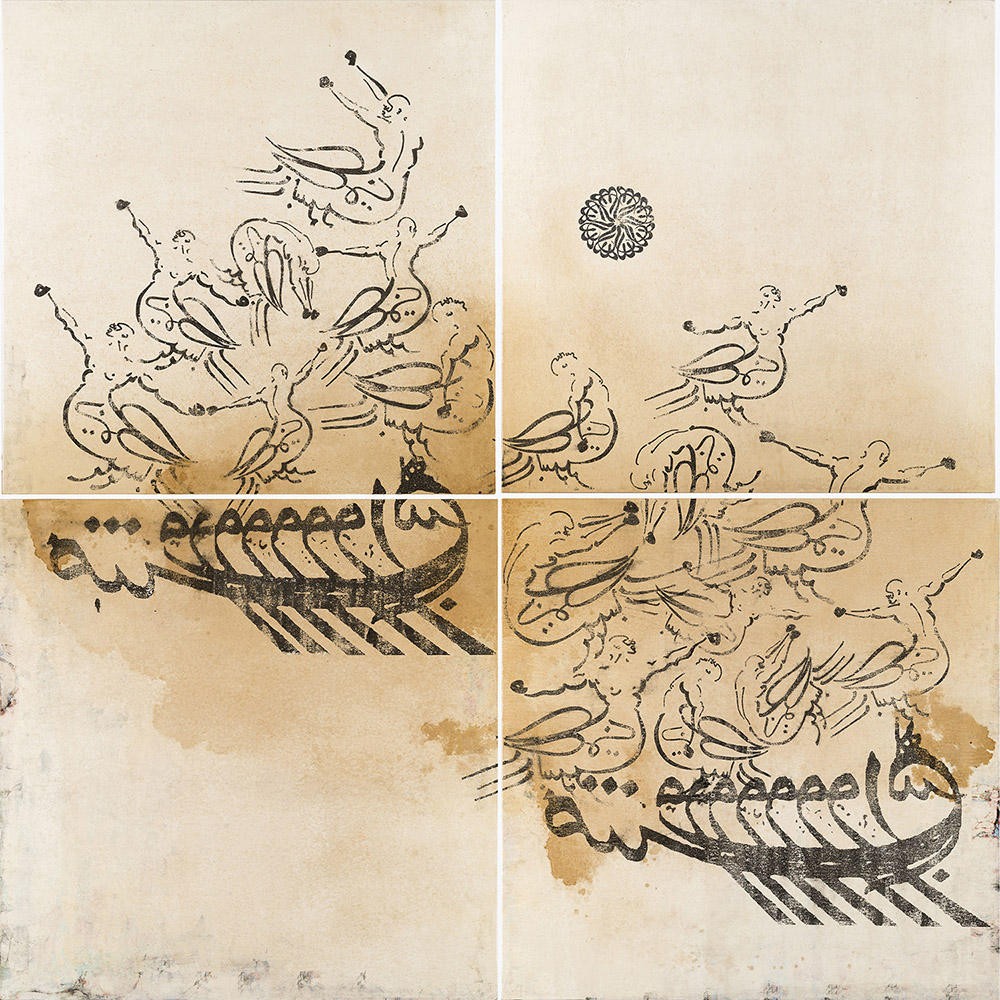

D. Y.: There is a partition amongst the paper works. For example, the quadripartite work, that is different than the others, independently unveils the images that only you have created, while the eightfold successive series presents a scenery where today’s problems are added to the climate of the events of the folk tales printed by lithography with their epic and battle legends. We cannot tell which one is real which one is fiction; these works transmit to us the feeling that all of it happens in simple present tense, the information that what happened in the past continues to happen “now” and the vision that what happens now, will encompass yesterday and tomorrow. In fact, they put forward the cyclical time concept that we observe in your entire art practice. In the perception of spiral time, we see you, painful of having witnessed today, in denial, desperate… as a Ravi trying to put across his message in a peevish, but decisive rush. We see the artist as a narrator.

December 2015, Istanbul

In his art practice that he shapes in an expeditionary thought system, Murat Morova creates his own myth, positioned “between” Western and Eastern mythologies. Crossbreeding, therefore mutating traditional art aesthetics within the framework of contemporary concepts, he creates a visual iconography of his own. The conversation with the artist on his solo exhibition “RAVi”.

Derya Yücel: We actually gathered to speak about your latest works, and solo exhibition yet unfortunately the trauma of terror from last night’s horrible events in Paris are with us today. These traumas are getting heavier as they recur, while our senses of justice and conscience are being damaged, and the incurable wounds deepen with daily politics like social injustice, torture, pressure, labor exploitation, and terror. On the other side, the annihilation of the Earth is in process showing its signs with climate change as a result of humanity’s irresponsibility towards the Earth/Nature, global warming, depletion of resources/species, etc. Thinking of this, we know that the themes you have been treating in your extended practice have been shaped around this problematic. The exhibition at Galeri Nev is called “Ravi”. Can we say that Murat Morova is a modern “Ravi” narrating today’s stories using the past’s metaphors with the language of aesthetics? You may want to start with the story that originated this exhibition.

Murat Morova: I would like to start with the accumulation that led to this exhibition. There is a “romantic” side to the exhibited works in relation to my personal history. As a kid, my grandmother and my mother would always take me with them when they would go shopping. Üsküdar, where I was born, was, just as is today, a more traditional district in the 1950’s; you could feel the link to the past whether because of that neighborhood feeling, or its examples of traditional architecture. People would sell different materials and products on the counters in front of the mosques. Religious books as well as social books would be sold on the counters. Folktales, myths, epic books printed with lithography containing stories on the battles of Hazrat Ali, epics of Seyyid Battal Ghazi, Tahir and Zühre, Kerem and Aslı, etc. would all have one thing in common: they would have narrative pictures. We would definitely buy some of these books, and they would affect me a lot thanks to its colorful, and naïve pictures, even though I did not know how to read at the time. These stories would have their specific literary tone. I remember The Battles of Hazrat Ali the most among these books; this is because Hazrat Ali was a character free of his time, and his stories would have a simple present tense perspective, encompassing all times. In some stories, he would go through events, or encounter other historic figures that did not belong to his period; the heroisms and religious narratives would blend together. Bandits, jinni, fairies, dragons, superhuman entities would accompany these stories. But the ultimate gist was always about the human virtue, feelings of justice and mercy, consciousness and generosity. There is always a moral. Hazrat Ali, in the belief systematic that he represents, has always been described as a figure that had all the features of a mature, good-hearted person, almost a perfect human being. He is the Eastern version of the savior hero cult, prevalent in most Western stories. Yet, he is more of a hero outstanding with his humanistic features, rather than his Western equivalents’ physical superiorities; like more beautiful, bigger, stronger, well built and superhuman. Hazrat Ali’s physical features many times carries a fictional exaggeration since they were told within a tale or legend.

D. Y.: Yet your figures do not create a heroic myth. I perceive your modest yet rebellious figures in relation with your personal and artistic state of remaining in purgatory, also with your state of being both inside and outside around the sensibilities that you equip yourself with. In a world buried in inhuman, hegemonic, exploiter, tyrannizer systems, your “perfect human being” image carries a part of all of us, trying to move in his own circle(s) with demands for justice, rightness, consciousness. How strong can we be in breaking this circle, and fighting with the one outside? We sometimes feel obliged to draw our own circle(s) to be able to create our shelters. This can be valid on a personal or societal level or even in the art field. We keep seeking other heroes to be freed from the challenges of yesterday, today and tomorrow. How did you transmit the stories at this exhibition? How did you shape Ravi’s voice?

M. M.: A man’s hero is himself. The issue here is being able to get acquainted with our own circles, and show the will to either break or to draw them. Although these are matters of utmost importance and urgency, in this exhibition I tried to switch on very simple, almost childish, and naïve concepts. I looked for the purest, least engaged states of this attitude of being a “perfect human being”; the new human typology, treating today’s traumas and problems like yesterday’s malicious enemies and monsters, and dealing with today’s evil, without any great ideological engagements. There is a narrator, a storyteller in all of these folk tales printed by lithography. This person gives reference to the “Ravi”’s as a basis for what he narrates. Ravi is the one who relates, tells, and sources. Firstly, he is a figure who transmits, carries the sayings/deeds of the Prophet in Islam. Of course, not all carriers, or narrators can get this title; to be a Ravi is considered as a degree. In time, “ravi” lost its meaning in religious etymology, and was widely used amongst people to describe anyone who told legends. Yes, I acted as some sort of a “Ravi” when narrating this exhibition. Because, fundamentally, the subjects of these folk tales - the malicious events of the past, the feelings of justice, consciousness, and mercy suffering from erosion, ongoing cruelties and raids- share the same bloodline with subjects of today. Although different in shape, they are conceptually the same. Therefore, my “Ravi”ness, stems from me, presenting the stories of today, in the form of those days.

D. Y.: Your ties with traditional aesthetics do not only appear on a physical level. In fact, the priority of your medium selection emerges at the point where it supports the content. With this outturn, you end up producing a decided work as a result of a rigorous selection with the aim of visualizing the content, message or story that you want to deliver. Therefore, although the surface aesthetics’ taste, arising from Islamic or traditional forms, is heavily present, it is not very possible to limit your works within one medium. Painting, sculpture, tile, ready object-installation, photography, collage… The form is supporting your story. The same can be told of your works in this exhibition.

M. M.: While revealing the works at this exhibition, I had to think of the level of the material’s naivety, and not of the aesthetics produced via today’s technology. I wanted it to have a form that gives a reference to the past. I was careful that they had the same color harmony as in the folk tale books printed by lithography, or the same paper texture. Therefore, in the 12 works that draw the main axis of the series, I used watercolor, drawing ink, powder paint, and some ageing techniques on handmade paper. I applied a composition in flu shades where you could barely see images referencing traditional forms. Surface aesthetics is an attitude outstanding in my production. I wanted it to have an illustrative taste without being caricaturized. I paid attention to this because the narrator who tells an illustrative story using a certain aesthetical language, while is a tradition in Western painting; it also is an ongoing taste at us. We may call it Eastern aesthetics, since our visual heritage until our encounter with Western painting is predominantly on the book surfaces. Like miniature, visual representation is an entity mainly supporting the text, the story. I do not own a touching work method based on inspiration, or born out of sudden impulse. My connection with the text during the process of research, collecting, reading, thinking, maturing and unveiling is very strong. The relationship of the works at this exhibition with the text manifests itself via the materials they take reference from. Sometimes, I choose to make use of several various mediums together in a solo exhibition, but this time I especially avoided that. There are paper works and canvas almost manipulated to look like paper. I tried to bring out the fragmentally metamorphosed surfaces. This is how we ended up with the two series consisting of 14 pieces in total. I used my own semblance in one of the 3 smaller canvas works exhibited at the entrance. My face appears on the form of a perfect human being, and on a figure fluttering wings with his/her own power, struggling, battling frenetically towards an action, a discourse.

D. Y.: There is a partition amongst the paper works. For example, the quadripartite work, that is different than the others, independently unveils the images that only you have created, while the eightfold successive series presents a scenery where today’s problems are added to the climate of the events of the folk tales printed by lithography with their epic and battle legends. We cannot tell which one is real which one is fiction; these works transmit to us the feeling that all of it happens in simple present tense, the information that what happened in the past continues to happen “now” and the vision that what happens now, will encompass yesterday and tomorrow. In fact, they put forward the cyclical time concept that we observe in your entire art practice. In the perception of spiral time, we see you, painful of having witnessed today, in denial, desperate… as a Ravi trying to put across his message in a peevish, but decisive rush. We see the artist as a narrator.