“Bir tarih yazmayı denesek hoşuna gider miydi?”

“Hiçbir şey bundan daha çok hoşuma gidemezdi! Ama hangi tarih?”

“Evet. Haklısın, hangisi?”

Gustave Flaubert,

"Bouvard et Pécuchet”

Londra, 1976

(orj.1899), s.123

Göremediğimiz Tüm Işıklar’da Burcu Yağcıoğlu, Deniz Gül, Hera Büyüktaşçıyan ve TUNCA’nın

sanatsal pratikleri dahilinde çerçeve içine aldıkları, resmi tarihlerden bireysel hikayelere,

hafızanın katmanlarından görsel sistemlere “bilgi”nin muğlak sınırlarını araştırıyor… Ve bu

sınırlarda gezinen hikayeler anlatıyor. Başlığını, Anthony Doerr’in aynı adlı kurgusal-tarih

romanından alan sergi, hafıza, gelecek, bilgi, kavrayış ve umudun metaforu olarak “ışığın”,

görülüp ulaşılamayan, hissedilip dillendirilemeyen, kavranıp anlatılamayan yanına dair bir

sezgi oluşturmayı amaçlıyor.

Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’ın, Bitmek Bilmeyen Bir Boylam adlı kinetik enstalasyonu, ahşap kaidenin

üzerinde üst üste duran ve ritmik biçimde aynı şekilde hareket eden iki bronz elden oluşur.

Büyük elin avucundaki küçük elin tuttuğu kiremit parçası, materyalin de ağırlığıyla, üzerinde

ileri geri hareket ettiği zemini aşındırır. Kalem tutmayı, yazmayı veya çizgi çizmeyi öğreten

bir ebeveynin eylemini anımsatan hareket, tarihe, dolayısıyla topluma sinmiş olan baskı örüntülerinin de bir sembolü olarak izlenir. El, hem bir kılavuz hem tahakküm simgesidir,

hem öğretir hem yönlendirir, unutmanın baskıyla, baskının hatırlamayla olan işbirliğinden

doğan tarihe direnmenin mümkünlüğünün altını çizer. Olayları ve olguları, zaman ve mekan

içinde sınıflandıran tarih, aynı zamanda şimdinin ve geleceğin deneyimlerini de organize

edebilir. Küçük el iz bırakır, tamamlayamadığı dairesel döngüsüyle toplumsal hatırlamaunutma

mekanizmalarına atıfta bulur. Kendi iradesi dışında gerçekleşen hareketi ile el,

bıraktığı izi her gün daha fazla kanırtarak derinleştirir. Sergide yer alan diğer bir çalışması

Geo-graflar (yeri-yazarlar)’da Hera Büyüktaşçıyan’ın sıklıkla kullandığı Bizans ikonografisi,

Vaftizci Yahya figürünün elindeki asasıyla merkezinde olduğu triptik deseninde bir kez

daha görünür. Atribük olarak bilgelik ve kılavuzluk metaforu ile asanın dikeyliği, karşısında

konumlandığı Bitmek Bilmeyen Bir Boylam adlı enstalasyonun mekanik hareketini sağlayan

direk ile ilişkilenir. Bu merkez desenin sağ ve solundaki desenler de sanatçının Hindistan

yolculuğunda, Amritsar’da karşılaştığı bir sahneden izler taşır. Sikh’lerin “Tanrı’nın Tapınağı”

dedikleri Altın Tapınağı çevreleyen suni gölün üzerini her gün toz zerreciği kalmayana dek

arındıran temizleyicilerden yola çıkan desende bir sandalın üzerindeki figürlerin altında

katmanlarca birikmiş kitaplar, tarihin oluşturduğu bilgi atıkları olarak belirir.

Tarih, eylem ve hatırlamanın sonucuysa, hatırladığımızdan başka tarihler yok mudur?

Eylemin gerçekleşmediği başka bir tarihi hatırlayabilir miyiz? Burcu Yağcıoğlu’nun

En İyi Yaptığım Şeyde Berbatım - Ve Sanki Bu Hediyeyle Kutsanmışım isimli diptik deseni,

sanatçının kişisel tarihinden akan imgeleri, içkin bir belleğin izleri olarak ortaya çıkarır,

sanatsal eylemin hatırlama ve bireysel tarihlerin kaydını tutma gücüne vurgu yapar.

Adını, Nirvana grubunun, bir zayıflığın, kusurun ya da eksikliğin güce dönüşmesini imleyen

bir parçasından alan desen, sanatçının çocukluk anılarında yer bulan bir evin istinat duvarı

ve bu duvarı kaplayan sarmaşık imgesinden doğar. Toprağın ya da yapının kaymasını

engellemek üzere yapılan ve işlevselliği olan ancak hep saklanan, örtülen ve gizlenen bir

yüzey olarak istinat duvarı, hem bir sınır, hem de birleşme noktasıdır. Gereklilik içeren ancak

saklanan varlığı gibi duvar, bu desenlerde de görünür olarak imgesel anlamda yer bulmaz.

Sanatçının ilk kez uyguladığı bir yöntem olan ve bu desenlerin de estetik temelini oluşturan

silme eylemi ile belirsizleşen duvar imgesi, desenlerin içinden çıkarak, çerçeveleri heykele

dönüştürür. Desenleri çevreleyen beton hem bir sınır, hem de bir bağlantı noktası haline

gelerek varlığını ortaya koyar. Tutunduğu duvardan düşmüş bir sarmaşık ve sirk kaplanlarının

çevrelediği ateş bu iki desenin ana imgelerini oluşturur. Alev çemberlerinden atlayan sirk

kaplanları gibi, çağımızın semptomlarında acıklı bir fenomen olarak tarih ve bilginin yapay

ışıkları altında izlenen birey, geçmişin yükünü hem taşır hem ona yaslanır.

Hatırlama, tarih bilinci ve tarih yazımının bir uyarıcısı olmuştur. Hatırlamanın ilk aracı

mekanlaştırmadır ve mekan(lar) toplumsal bellek pekiştirme işlevinde başroldedir. Özellikle

anıt-mekanlar, tarihin göstergeleri olarak işlev görür ki ölülerin anılması, hafızanın,

dolayısıyla tarihin toplumsal ortaklıklar yaratmasında önemli bir olgudur. TUNCA’nın

İsimsiz desenleri, Auschwitz’in üç kilometre batısında bulunan Brzezinka (Birkenau)

bölgesindeki kamp içinde oluşturulmuş bir anı duvarından yola çıkar. Sanatçının,

bölgeye yaptığı gezilerde ziyaret ettiği bu anı duvarı, 2. Dünya Savaşı döneminde

kamplarda hayatını kaybetmiş veya yaşamış insanların sahiplerine ya da yakınlarına

ulaşamamış eşyaları arasından çıkan fotoğraflardan oluşturulmuştur. TUNCA, hatırlamanın

hatırlanmasına katkıda bulunarak, kendine özgü plastik diliyle bu duvarı yeniden meydana

getiririr. İzleyicinin mesafesi ise bir başka katman olarak işler. Uzak bir bakışla detaylı

olarak görünür olan bu isimsiz yüzler, yakınlaştıkça netliğini kaybetmeye, belirsizleşmeye

başlar. Yüz, kimliğin tanımlandığı en özgül alansa, bu portreler tıpkı ortak hafızalar gibi

ortak kimliklerin yaratılmasına yönelik çabanın muğlaklığını anımsatır. Geçmişin ölüler

kuyusundan çekip çıkarılan portreler, yabancı olanı değiştirip yeni bir biçime sokar, birleştirir,

yarayı sağaltmak ve eksiyeni bütünlemek için kırılıp dağılmış olanı yeniden görünür hale

getirir. Kendisini hatırlatan bir nesnenin (fotoğraf) anımsama fragmanları olarak, bu anı

duvarından mekana saçılırcasına çoğalan desenlerde, yıkım, yitim, eksiklik ve sürekli olarak

artan bir hatırlama sıtması içinde kıvranan bir tarihin içinde zamana karşı, zamana uymayan,

umutlu bir dilekle zamana etkide bulunmaya girişen bir yön de vardır.

Tarihin doğurduğu en haksız durum, geçmişe karşı bağnaz, belirtiler karşısında sağır,

korkular karşısında kör, unutmanın ölü denizinde kayıp olmanın bilincini taşımaktır.

Deniz Gül’ün Bir Çiğdem Tarlasında Zikrini Sürerken Devam Ediyorduk Aşkımıza Öylecek

isimli 3’12” süreli videosu “Yalan!” kelimesiyle başlar ve izleyici, sanatçının kaleme aldığı

metni bir monoloğa dönüştüren karakterin zihninde gezinir. Görülen, geniş bir uzam

olarak çiğdem tarlasının ortasında gerçekliği meçhul ve uçucu bir sahnenin faniliğidir.

Figürün keskin mimikleri ve bedensel jestleri görsel-işitsel olarak törensel bir sahne yaratır.

Bir tür ritüelin tanığı haline gelen izleyici, yabancıyı önce bulanık, anlamsız bir ses gibi

duyar ama bir süre sonra o sesi (kelimeler-cümleler) yakın, çınlayıcı ve aydınlatıcı olarak

anlamlarıyla kavramaya başlar, ya da sanar. Bellek, tanıdık bir kelimeyi çekip seçmeye

zorlanır, duyulduğu sanılan sesi, cümleleri ayıklamaya çalışır. İzleyici de kurgusal bir

dilin, teatral bir öfkenin ve dramatik bir atmosferin içine çekilir. Video, bilginin ve tarihin,

kırılgan ve kaotik tarlasında yönünü ve anlamını yitirmiş bir şimdinin sembolü olarak

izlenir. Tarih çok uzun zaman iktidar ve kazananlar tarafından yazılmıştır. iktidar da kendini

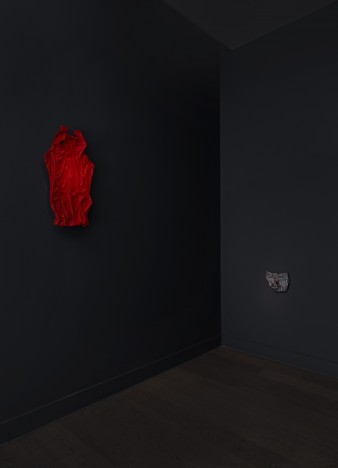

onaylatmak için menşeye ihtiyaç duyar. Bu nedenle tarih, kanıtları sever. Deniz Gül'ün

sergide yer alan ve gündelik nesnelere yeni anlam katmanları aktardığı Don-Atlet isimli

heykelleri de mekanda tarihsel kanıtlar gibi konumlanır. Sanatçının, sertleştirilmiş erkek

iç çamaşırlarından meydana getirdiği, don ve atletleri birer heykele dönüştürdüğü işleri,

arkeolojik birer buluntu gibi müzeolojik bir sergileme formunda izlenir. Erkek iç çamaşırları,

ister siyasi ya da toplumsal ister ekonomik ya da kültürel, iktidar ve tarih yazımı ilişkisinde

patriarkal sistemlere işaret eder.

Tarihin aşırı bolluğu içinde kimi zaman tarih dışının peşine düşen sanat, olduğu iddia edilen

gerçekliklerin o ince örgülü ağından kurtulup yeniden kıvılcımlar saçan bir ışığı yakalayabilir

mi? Tarihin tekinsiz bahçesinde cesur ve başıboş bir ateşböceği gibi yönünü bulabilir mi?

Söndüğünü gördüğü ışığı imrenerek bekleyebilir ve bu umudu aktarabilir mi? Anlamı-anlam

dışını üreten sanat, tarihlere karşı tarihler yazabilir mi?

“Tarafsızca yargılayabilmek için bütün tarih eserlerini,

bütün anıları, bütün günlükleri ve bütün el yazması

belgeleri okumaları gerekecekti, çünkü en küçük

bir hata ya da eksiklik sonsuza dek diğerlerinin

oluşmasına neden olacaktı… Vazgeçtiler.”

Gustave Flaubert, “Bouvard et Pécuchet” *

Londra, 1976 (orj.1899), s.121

Gustave Flaubert, “Bouvard ile Pécuchet / Bilirbilmezler”, Çev. Tahsin Yücel. Can Yayınları, İstanbul. 1990